Love, Lucy is the New School Free Press’ weekly advice column, where writers anonymously share thoughtfully researched solutions to your questions about life. Send submissions through Love, Lucy’s official Google Form, and you might hear back from Lucy herself.

Dear Lucy,

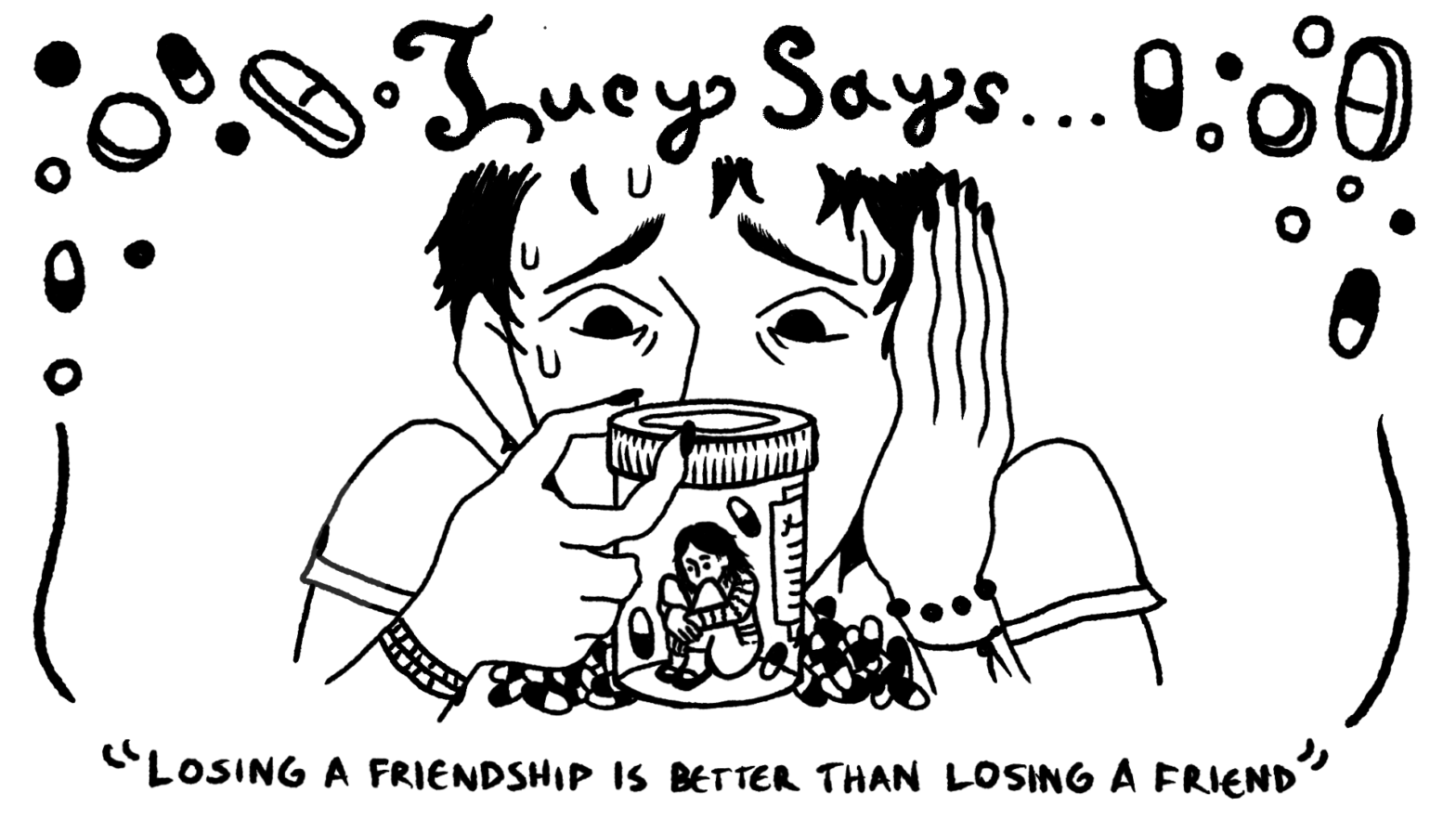

My friend has a drug problem. How do I help without overstepping?

Sincerely,

Cautious Carer

Dear Cautious Carer,

I’d like to first say that 1) I’m so sorry you’re going through this and 2) you’re very brave. Watching someone you love hurt themselves is excruciatingly painful and getting them help can be exceedingly difficult too. For what it’s worth, I’ve been where you are, and nearly six years of hindsight have taught me a few things about how I would handle the situation differently now.

When I was eighteen, my childhood best friend overdosed on my lap at Lollapalooza after ingesting a hair-raising cocktail of drugs. Although I’d been watching her active addictions to Xanax, weed, and alcohol ravage her body and life for almost a year, I was shocked, frozen, and completely ill-equipped to spend the next ten hours with her in the hospital handling the aftermath. And right after, “I don’t know what I’d do if anything happened to her, please just let my best friend be okay,” my next immediate thought was, “If I had just done the uncomfortable thing, maybe this wouldn’t have happened.” Thankfully, she was okay, but I was still terribly shaken and wracked with guilt.

To blame oneself in the face of another person’s self-destruction is a natural and normal response, but it’s not always a helpful or even logical one. Oftentimes nothing anyone says or does can really affect a person’s behavior until they’ve simply reached their own limit. Most people refer to this as their “rock bottom.”

Maybe there were times when you could have said more or been more brutally honest, but it was just too atrociously difficult to be candid with someone you love. Try not to blame yourself if you’re already in this position. I’m sure you’ve done your best.

But if things haven’t quite reached their hellish peak and you still have time to intervene, here’s what I’d suggest:

You mentioned that you don’t want to overstep, and while I understand your worry, you have to think in black-and-white terms right now. It’s probably impossible to help without “overstepping” because to a drug addict, anything that even remotely disrupts their ability to maintain their lifestyle (i.e. help, brutal honesty, worry from loved ones, etc.) is going to be considered overstepping.

No matter how detrimental, dangerous, or risky it is, addicts rarely ever see their behavior as problematic. If they do, they’ve probably reached a certain state of complacency about it. So no matter how “right” your actions are or how measured and “reasonable” your help is, they’re probably going to see any form of intervention or expression of concern as a betrayal of their trust and a threat to their way of life.

Though I’m not proud to admit it, there were times when I unequivocally enabled my best friend’s drug problem. It wasn’t on purpose — I was eighteen and had no experience keeping an addict in check — but I also knew that failing to voice concern about her behavior would only encourage it to continue. The last thing I wanted was for her to think I condoned her actions, but we used to smoke and drink casually together before things became a real problem, so wouldn’t I seem like a hypocrite with no leg to stand on?

Even if you’ve partied together in the past, that doesn’t make their identifiable problem a gray area. As a friend and support, you still have the right to express how their alarming behavior is affecting you and making you feel. None of these conversations will be easy. There’s no way for me to sugarcoat it. But the upside is that you might help save your friend’s life or at least do your best to set it down a better path.

Your friend’s health and safety is priority number one, no matter what. So you have to do what will protect them even if it might jeopardize your friendship. “Telling on them” or getting them help might make them hate you now, but if it keeps them safe, then it’s probably better to have a living acquaintance than a dead friend.

Since handling this situation is so heavy, it’s in your best interest not to go it alone. Recruiting a few other members of your friend’s support system (i.e. other family, friends, and close loved ones) to help you in your endeavor should both take some of the weight off of you and reinforce to your friend how valued they are.

Your friend is likely not in a great mental space right now (at least statistically), so expressing how much you love and care for them is a great start. And as experts recommend, always make sure everyone involved in the conversation is good and sober.

Establishing an open dialogue, as corny as it sounds, is the key to success in this kind of conversation. And notice that I’m calling it a conversation because that’s just what it is — not a lecture or a reprimand or a guilt trip. It’s really important that your friend feels heard and not judged because they’ve likely felt a decent amount of shame to begin with. Listening to those closest to you detail all the ways in which your behavior has scared, upset, or otherwise negatively affected them is no easy feat, and it’s exactly what your friend is going to have to do.

As uncomfortable and painful as it is to tell the ugly truth, I’m quite sure it would be worse to realize you could have done more when it’s already too late. And though you might lose their friendship for a little while if you “overstep” now, it’s better than losing them altogether.

I don’t want to give you false hope or an unrealistic template, but I do think it’s worth mentioning that after everything, my friend and I are on really great terms. We didn’t speak for almost a year and a half after I spilled everything to her brother and mom in the ER waiting room, but she eventually thanked me for giving up information to her mother that probably saved her life — even if it did get her grounded for nearly a year at the time. She still drinks, but she’s been clean from Xanax for nearly three years. I consider that a victory.

So if you want the abridged version, if you want to save your friend from their addiction, you have to let go of the fear of “overstepping” and focus on the fear of losing them. Whether they thank you immediately, years down the line, or never, you’ll always know that you did all you could to protect and support them. Maybe that’s reward enough.

Take care of yourself, Cautious Carer, your heart is noble and true. Don’t forget to look after it too.

Love,

Lucy

***If you or a loved one are struggling with addiction, there are many resources to assist you in seeking help. Call 988 or visit SAMHSA’s National Helpline to start. ***