What have you accomplished in the last 24 hours? For Mother Figure Comedy Collective, their Sunday night answer might surprise you. From 6 p.m. Saturday, April 19 to 6 p.m. Sunday, April 20, they didn’t sleep, subsisting off of KitKats and cold brew, locked in a room on the lower level of The New School’s University Center, making a musical. Both the beauty and the inevitable obstacles of the project were wrapped up in its participants — an ensemble of deeply funny creatives brimming with ideas, itching for laughs, and on little to no sleep. Mother Figure Comedy Collective is made up of students across majors, from the Eugene Lang College of Liberal Arts, the College of Performing Arts, alumni, and former students.

On Saturday night at 6:00 p.m., April 19, Lily Shafer, executive board member of Mother Figure, starts the clock. Half of the registered participants of the collective’s inaugural 24-hour musical — a ten-scene, original production written, composed, and brought to life over the course of 24 hours — are sitting in their seats in Starr Foundation Hall. A flotilla of messages is sent out to the missing members, and responses slowly filter in — the L train is delayed, there was a last-minute group project, and someone was too tired. Shafer congratulates those who were there on time and declares that at 6:15 p.m., they’ll really get down to business. “People are dropping like flies,” she jokes. The group begins discussing how to embark, and the production’s music director Yarrow Hachey — coming off of a 9-5 shift — implores the collective to vote for the clearest idea, set in the most interesting world.

At 6:18 p.m., pitches begin. A larger group of Mother Figure members had come up with five broad concepts at a workshop on Monday evening, April 14. Ideas include: a liberal arts seminar at a university on the verge of a faculty strike (sound familiar?) in the vein of Heathers and The Breakfast Club; a drag-queen-frat-boy love story set during a will reading on a cruise ship; and a factional drama set in a tiny house community outside of Philadelphia.

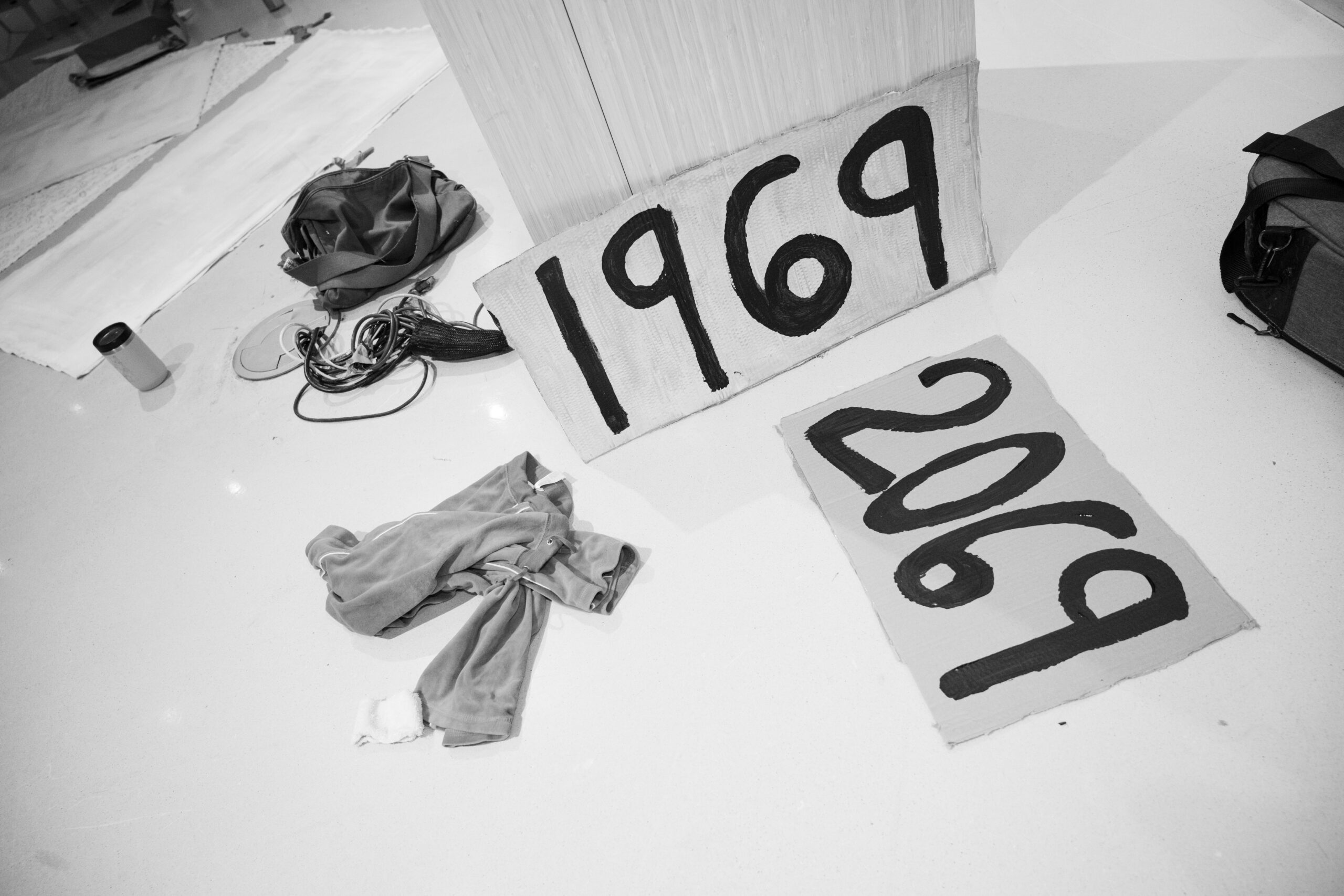

At 6:36 p.m., voting commences. The winning idea, pitched by Sam Levy, is titled Breakpoint 2069. The story starts at the 1969 U.S. Open, where fictional tennis player Merick Bozeman attempts a risky move and falls through a portal 100 years into the future. The U.S. is now the United States and Associated Corporate Entities, and the game of tennis is king. Bozeman falls in love, makes friends, kills, and wins, eventually falling back onto the court in 1969.

At 6:39 p.m., Levy runs off to find a whiteboard, and Hachey throws out some writing tips. “Keep a beat in mind. We need to give something to the band. If it’s just the words, it’s going to take a lot longer,” Hachey says, laying out some guidelines to avoid chaos later on. 39 minutes in, and time constraints are already on everyone’s mind.

At 6:42 p.m., while laying out the length of the scenes, the group realizes that ten 10-minute scenes won’t result in an hour-long performance. Scene length is cut to six minutes each. It’s going to be a long 24 hours.

At 6:45 p.m., I check in with the group — what are your early thoughts? What are you feeling nervous about? “The stakes are pretty low to me,” Executive Board Member Nora Iammarino says.

“I’m scared of how many times we’re going to get asked to perform it again,” Hachey jokes. Shafer tells me that last night, she had a dream in which an incredibly talented young actor-writer joined the collective and then pulled out in the wee hours of the morning.

At 6:49 p.m., the last of the stragglers arrive.

At 6:54 p.m., writing begins. The outlining of scenes and characters takes place on a whiteboard at the front of the room — Levy leads the charge with an Expo marker in one hand and a Red Bull in the other. Iammarino is taking notes in a shared Google Doc — when the collective splits into writing groups, continuity and communication will be key. Yarrow, Shafer, and Levy exercise veto power when necessary.

At 7:08 p.m., casting starts. Things come together fairly quickly; the group knows each other’s strengths and weaknesses.

At 7:13 p.m., writer-musician Tyler Phillips reveals that his parents made him watch a lot of tennis, and he played it in high school. He is quickly dubbed the resident tennis expert.

The collective doesn’t shy away from references; Idiocracy, Futurama, and the Onion’s future news YouTube video are offered up as inspiration for Breakpoint 2069.

At 7:34 p.m., Levy discovers that the acronym for the futuristic country is U.S.A.C.E. — “ace” being a tennis term for an unreturned serve — and the group erupts in applause. Immediately after, Levy redirects, “We’re getting into the weeds. Let’s fill out these scenes.”

“We’re not writing” is a frequent mantra uttered throughout this outlining process. The collective doesn’t get bogged down in the details of dialogue or director’s notes during this crucial aspect of the night. Writing is for later — 8 p.m. to 1 a.m., to be exact.

The group discusses the motivations of characters named Point, Sneek, and Foot in a world where tennis matches to the death take place on the Kroger Court. Surprisingly, there are some pretty deep considerations of the theme. The collective asks questions like, “What does it mean to win? What does it mean to be good? Does being good mean different things in different worlds?” Quickly, the team has sunk into the world of Breakpoint 2069, and central themes begin to surface — love, corporate greed, and familial pressures.

At 7:52 p.m., the word Macbeth is uttered — in the theater where they’ll be performing the musical in just 22 hours and 8 minutes. At 7:55 p.m., Macbeth is said two more times. Maybe that cancels out the bad luck?

At 8:07 p.m., the team splits into three groups to get down to the nitty-gritty of writing. Each group is assigned a few scenes, and writing begins in earnest.

Group one, left in Starr Foundation Hall, uses a piano and a guitar to compose key scenes 1, 2, and 10. Group two, in the Bob and Sheila Hoerle Lecture Hall, is in charge of scenes three and six, and any others left up for grabs. Group three, in a nearby computer lab, is handling romantically-charged scenes four and eight, and at 8:24 p.m., they’ve projected an image of Art and Patrick from Challengers onto every wall of the computer lab. A clear tone is set.

At 9:25 p.m., a security guard comes into the hall. “The event ended at nine, right? You guys are supposed to be out of here?” he asks. The group blanches. Things are just getting started. Throughout the first hour of writing, musicians and set designers begin to arrive.

At 9:32 p.m., the collective remerges. Group one gathers around the piano to present the opening number. While the collective listens, set designer Elle Gallen begins taping sheets to the walls. Things are coming along nicely — the mood is light. Ideas are flowing. Tennis puns are still getting laughs.

There’s no shame in feedback — lines are cut and added with cheers and claps abound when great moments break through. Shafer keeps time. Disputes over plot consistencies are settled easily and with humor. Levy is focused on the futuristic satire. “Throwing in an ad or sponsorship is kind of funny but not funny enough,” he says. “How can we elevate it?”

The groups are released to continue writing. The next check-in is scheduled for 11:30 p.m.

At 11:28 p.m., the collective regroups once again, feeling slightly stuck. “I think this is the obstacle we anticipated. At some point, the songs we write have to become songs,” Hachey said. The musicians are committed. Lollipops are in mouths, and chairs are clustered around the piano.

This point in the process is an exercise in translation, turning ideas into words, words into music, and music into performance.

The next task is consolidation, tying off inconsistencies, and maintaining a tone. “Because we’re writing the scenes in isolation, they aren’t building in stakes,” Hachey says. “There’s a lot of overlap,” Levy agrees.

At 11:47 p.m., Levy suggests picking up a gallon of cold brew and some cups from CVS. They’re writing reprises. Comments line the margins of the Google Doc.

The mood in the room lifts when the collective is singing and running through scenes — things only sour when they’re forced to consider logistics. It’s easier to sink into the words and music than it is to hear a reminder that there’s nearly 6 hours gone and 18 left to go.

At 11:55 p.m., Levy confers with Hachey, working alongside the musicians. “Any shortcuts you can take, do it,” he explains.

At 11:58 p.m., the writing team is down to the last few scenes. There’s a lot of work left to do in terms of composing. The Starr Foundation Hall has been transformed into a makeshift studio complete with a guitar, piano, a chorus of voices, percussion, a table laden with snacks and props, bags scattered against the walls, and water bottles rolling across the floor. Two different songs are being composed on opposite sides of the room. Shafer writes an updated list of scenes on the ever-present whiteboard. Somehow, everyone seems to need a phone charger at the same time.

At 12:27 a.m., Shafer checks in. “Do we think we’re good for a 1 a.m. stumble through?” she asks. “What does that look like to you?” Hachey replies.

At 12:40 a.m., the writers joke that absolutely none of this will make sense in the morning.

Writer and actor Amy Sihler is doing handstands against the wall. Iammarino is brewing tea in a kettle plugged into a wall outlet, and Adina Alterman, writer and actor, is filming footage for a documentary class final. There are 17 hours and 11 minutes left until showtime. “3 to 4 [a.m.] is going to get dark,” Immarino predicts. Sihler begins to worry that she’ll lose her voice.

At 1:01 a.m., everyone begins flowing back into the room for the first full read-through. It’s loud with chatter. Shafer walks the crew through the next few hours and explains that Levy, Hachey, and Iammarino will give notes on the table read. No one else is allowed to give notes, to keep the process streamlined. The production has a real risk of too many cooks in the kitchen.

At 1:06 a.m., the first readthrough begins. Things run pretty smoothly, considering it’s an hour of material, music included, written in seven. Applause resounds after each scene, and the musicians embrace the energy, improvising for scenes where the music has yet to be written. Breakpoint 2069 is starting to feel less like an idea scribbled on a whiteboard and more like a thing taking up space in the room.

1:40 a.m. marks the swift pivot from performance to feedback. The room is attentive to dynamics, exposition, rhythm, and plot development — one of the benefits of writing a musical in 24 hours is that no one gets too attached to any one idea. After notes, it’s time for rewrites, music, and rest until 4 a.m., when staging is scheduled to begin.

I’m struck by the cross-disciplinary quality of the night. Musicians, costumers, set designers, writers, and actors from across TNS are working incredibly hard to get this done. Individual talents are colliding at high speed, but a vision is certainly coalescing. These 24 hours aren’t just a crash course in constructing a musical — they’re 24 hours of intensive teamwork.

In this vital writing phase, Mother Figure Comedy Collective truly gets a chance to flex its comedic chops. Words and ideas move quickly, competing for airtime, and it’s not just because of the time constraint. Their work isn’t without self-awareness, however. At one point during early run-throughs, Hachey offers up an important piece of criticism: Are the puns and joking speech impeding narrative clarity? It’s tough to walk a line between a densely humorous script and a conceivable plot, just as difficult as it is to balance an efficient workflow against an amiable environment.

“The brevity in which we speak to each other is not a reflection of how we feel, as it is how little time we have,” Hachey says, late Saturday night. “No time for apologies,” Levy says. These interpersonal considerations are an important aspect of the process — part of the magic of the collective is its close-knit relationships. They’re friends on and off the stage.

At this point, I have full faith in the success of the production.

I return to the Starr Foundation Hall at 9:38 a.m. “Everyone’s stepping it up in a great way,” Shafer says, looking no worse for wear. “But they’re also falling asleep on their feet.” Several people have gone home to sleep — Hachey says they’re taking shifts. “If they recognize their moment is not right now, they’re good to take a break.”

At this point, they’ve been blocking since 4 a.m. They finished around 6:45 a.m., and they’ve been running scenes since. They’re on scene 9 out of 10. Around 4:30 a.m., Hachey says her vision started to go. A five-minute nap at 7 a.m. and a Dunkin’ run solved that problem.

Around 7:30 a.m., printed copies of the script populate the hall, and a few hours later, the collective finds a stapler — a thrilling development.

The band is going strong. They took a break and got some sleep from 5 a.m. to 7 a.m., although Shafer says that no one has slept for more than an hour at a time. “It’s really impressive what they’re able to pick up,” Hachey says. “It’s been easy to get on the same page.”

At 9:51 a.m., Hachey steps aside with Cooper Traluch, who plays tennis supervillain Jokavich Prime, to do some Russian accent work.

The next hurdle, according to Shafer and Hachey, is tech. They’re looking to implement lighting, get the full band going, and start doing things in costume. At this point, canvas sets are drying on the floor, and more pieces are in progress in the Making Center upstairs. Sihler is refreshed by a 32-oz cold brew. “Once you push past that point of exhaustion, you get back to normal,” she says.

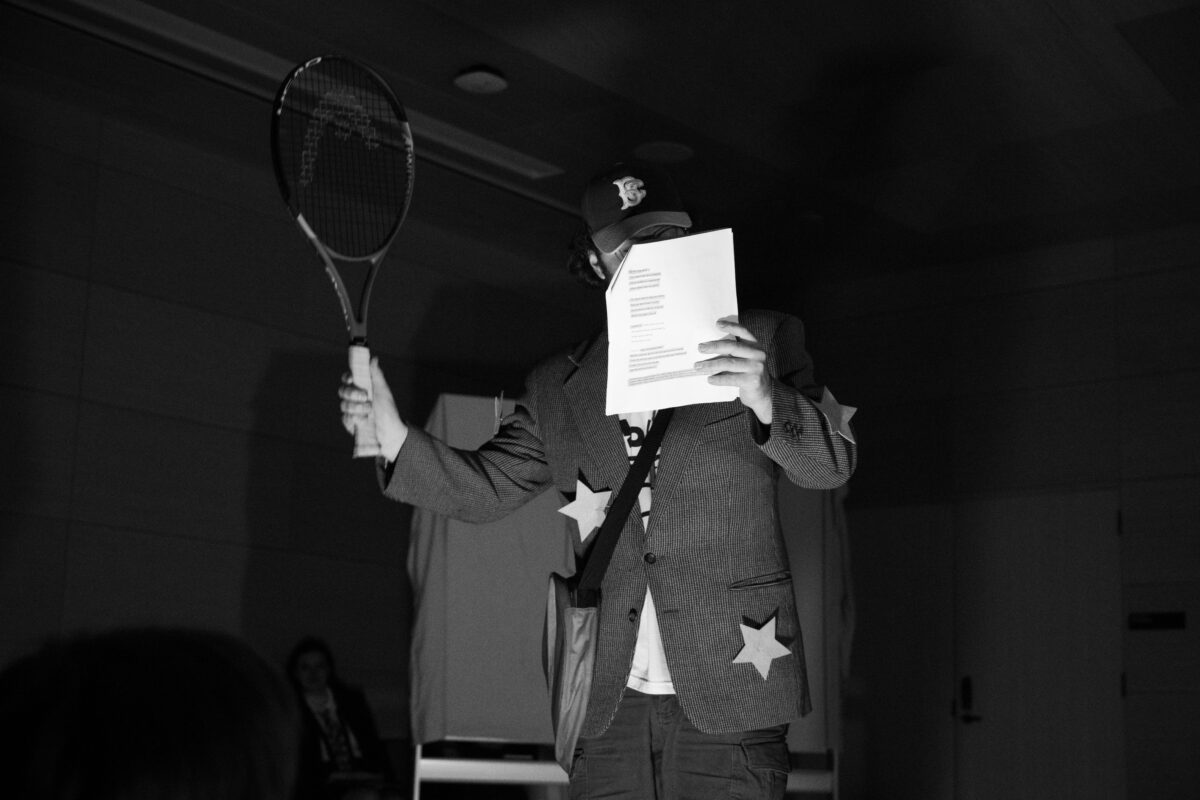

It’s 10:41 a.m.. There are 7 hours and 18 minutes left until showtime. The drum set is being assembled, and actors are pacing and reciting lines, while Shafer is organizing props — tennis rackets, sparkly faux tennis balls, and foam fingers.

As the hours pass, the vision has clarified. It’s futuristic, but it’s grounded in reality. It’s satirical, but there’s a real heart to it. “I like that our music is all sorts of Americana,” Levy mentions.

“The fiddle is giving us this beautiful bluegrass sound,” Hachey says of the newest arrival, fiddler Jackson Earles’ contribution to the band.

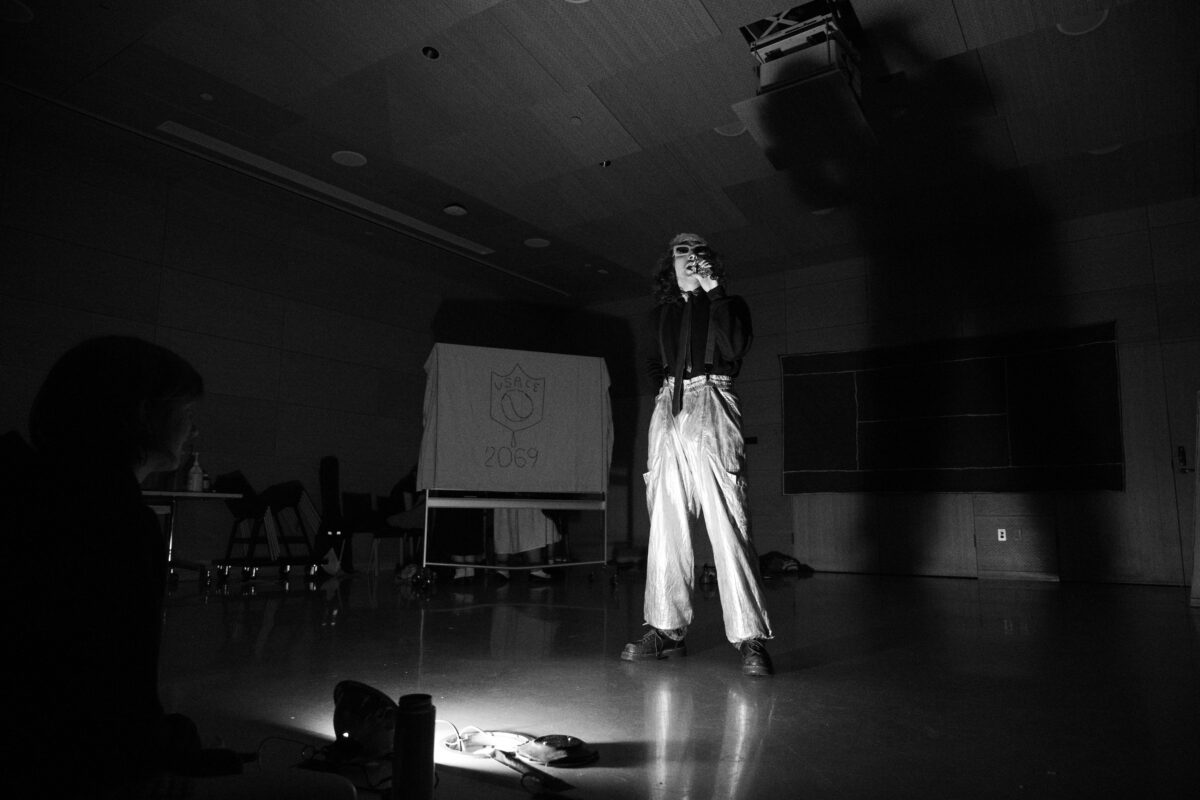

At 11:08 a.m., the group gets into costume. Spirits are high; cast members are jumping around as tin-foil hats are donned and suspenders are tightened.

At 11:11 a.m., the first stumble-through begins. Auspicious. The energy is there, even if all the words (and actors) aren’t. As the performance progresses, the holes in blocking and memorization reveal themselves. Shafer and Hachey provide some notes, asking for energy and confidence. After notes, the actors break until 2:30.

By 2:16 p.m., some of the sets are up — sheets are draped over whiteboards, and tables are tipped on their sides and covered in cardboard painted to look like lockers. Keefer Glenshaw, cello player, has arrived. 3 hours and 44 minutes until showtime. With the drum kit set up, a full crew of musicians present, the lights dimmed, and the table of snacks and piles of backpacks pushed out of view, it’s starting to feel like more of a place where a production might happen.

Writer and cast member Damien Fox reads New York Times Lifestyle headlines into the microphone at the front of the room. Gallen has been battling with the backdrop, trying to keep it attached to the wall. Cast members mill around, motioning through choreography, reciting lines under their breath, all a little manic.

At 2:31 p.m., Traluch is lying on the floor, cheek to linoleum. Becca Moore, writer and lights technician, reviews light cues and scene transitions with Iammarino. Sihler’s voice is nearly entirely gone. “I’m leaning into it,” she says. “My first song is kind of Tom Waits, and my second is kind of John Prime.” Cups of cold brew litter the floor. “It’s so sad that we’re only doing this [show] once,” Levy says. Hachey’s asleep, presidential hat heavy over her brow.

The first run-through after the break is for figuring out the lights and punching up the choreography. “Save your voice on this one,” Shafer says. Remember to pause after you say something funny, she adds — “During the show, people might laugh.”

At 2:42 p.m., Phillips arrives with a canister of tennis balls — the first real tennis balls to grace the room, despite the fact that it’s been a tennis musical since 6:36 p.m. yesterday. I am deputized by Levy to run out and grab a box of Throat Coat tea. Sure, journalistic neutrality, but at this point, I’ve grown to feel for the cast, and after 20 hours and 42 minutes, they deserve it.

At 2:54 p.m., the first full tech run-through begins. It’s definitely a musical, and the actors are mostly, kind of, off-book. Shafer stands in the center of the audience, facing the stage, surveying the progress. At this point, it’s a matter of stitching it all together — music, lights, the words, the sets, the movement. The addition of clamp lights at the front of the stage creates larger-than-life shadows that flit across the back wall. It’s shadow puppets, it’s guerrilla theater, it’s folk and rock & roll.

3:25 p.m. Levy heats up the kettle for a round of Throat Coat. The band requests another run at scene three.

I’ll give it to them — every minute that passes, every time a scene is retouched, every part of the show gets better. No plateaus here. There hasn’t been a moment of stillness since 6 p.m. Saturday night.

At 4:23 p.m., the collective practices their bows. It’s electric. People are excited and ready. Yarrow facilitates a vote: “Who wants another full run-through?” There’s a majority agreement to go for it again, and the group breaks for a brief bathroom break.

At 4:38 p.m., 1 hour and 22 minutes until showtime, the final tech rehearsal begins.

As a few writers and friends of the cast trickle in to watch the tech, it’s refreshing to hear laughs from the long-empty seats. After 23 hours, the collective has grown blind to its own material.

At 5:24 p.m., final tech finishes. The house is set to open at 5:45. Everyone jumps into final actions: Yarrow has notes for music, the floor needs to be cleared of detritus, cups of hours-old cold brew are dumped out.

5:47 p.m. 13 minutes until showtime. Shafer says she’s not nervous — she’s sure it’ll go well. “We’ve practiced a lot at this point,” she says. “It was 24 hours, but it felt like no time.” She heads to the front to offer some motivational words. “It’s beautiful, you’re all beautiful,” Shafer says to the collective. “I’m on my sixth wind,” she says.

Levy chimes in with some wisdom from a 24-hour musical advice Reddit thread — sure, you’ll all be exhausted, but that’s what the audience came for. I ask Shafer if she’d do it again. She pauses and then shakes her head. “Just because this is the only group I’d want to do it with.”

At 5:51 p.m., Moore hits play on the pre-show hype song: “Turn My Swag On” by Soulja Boy. A quick dance circle to warm up and reignite the energy that has ebbed and flowed over the past day.

At 6:15 p.m., the lights dim, and the performance begins. It’s a packed house — around 40 audience members are seated in Starr Foundation Hall. The performance is raucous: attendees cheer, hoot, and holler. It almost feels like the audience at a real tennis game as the characters rally lines back and forth across the stage.

At 7:02 p.m., the cast takes their bows to the tune of a standing ovation — somehow, the actors stay on their feet. The audience flows out into the event cafe, waiting to congratulate the cast and crew. “It was a beautiful way to end and commemorate 4/20 and Easter,” third-year photojournalism student Keegan Stewart said.

“The music was incredible,” Mimi Huelster said, a second-year student at Lang.. “I was expecting a jukebox musical.” Huelster knows a lot of the collective’s members and came out to support her friends. Could you tell they put it together in 24 hours? I asked. “Yes, but in the best way possible,” Huelster responded. “It fits the brand of Mother Figure.”

And with that, the 24-hour process is over. It ends on a celebratory note. Mother Figure set out to make a musical in 24 hours, and through exhaustion, debate, technical difficulties, the limits of the human body, and the complexities of artistic collaboration. They did just that. Long live Breakpoint 2069, never to be performed again.

Leave a Reply