The New Review is a biweekly series where writer Kayley Cassidy will examine an art installation or exhibition close to The New School campus. This week, she spent time breathing in the salty air at Hudson River Park, reckoning with the haunting past in “Day’s End” by David Hammons.

As college students, I’m sure you’ve all experienced early semester burnout at some point in your academic career. Coming up with different ways to combat this struggle is challenging, especially when you’re still trying to figure everything out. Take advantage of the city during this time and leave campus. Just a 10-minute walk from The New School can give you a well-deserved break at Hudson River Park.

The waterfront will satisfy all your needs. Let the pungent, salty air of the Hudson clear your clouded senses. Along the four miles of piers, there’s something for everyone: gardens, restaurants, recreational spaces, walking paths, and a view of New Jersey (if you’re into that).

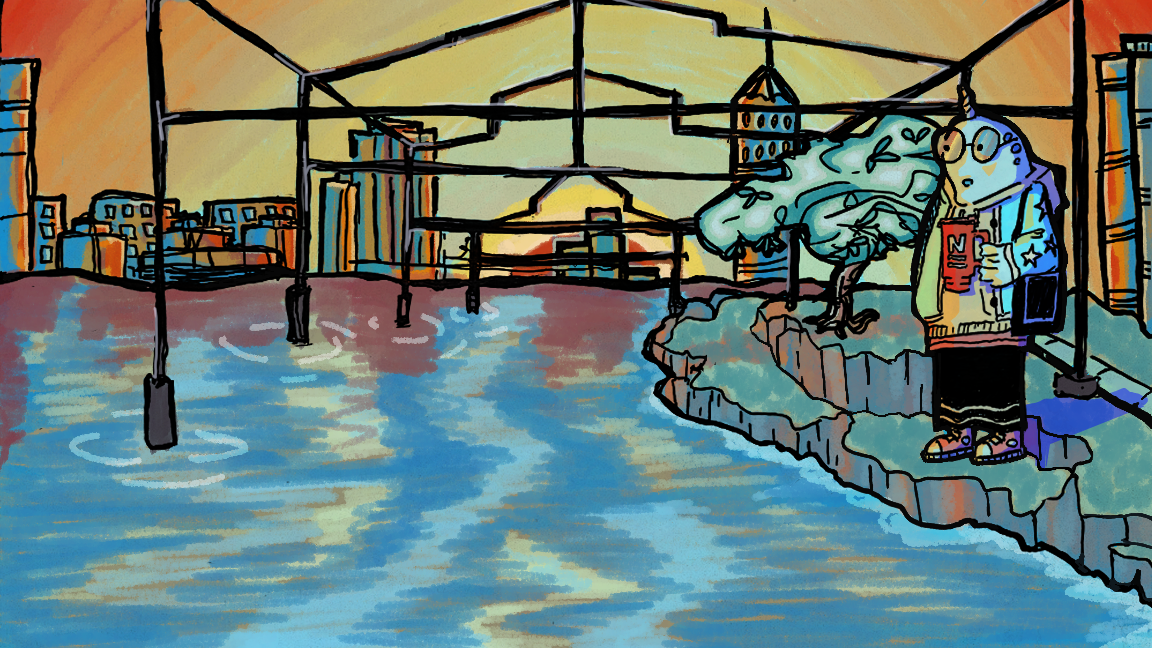

If you walk north up the pier, you’ll come across a row of six steel poles shaped in the outline of a shed cemented into murky waters. The poles shine throughout the day and stand out amongst the late afternoon sunset. “Day’s End” by David Hammons is a skeleton of New York City’s past. Water churns around the grounded cement, clashing against large rocks. Observe the structure by sitting in the bright blue beach chairs at Gansevoort Peninsula, where New Yorkers can simulate a day in the sand.

I challenge you to put yourself in the environment around you, around these steel poles. Listen to the water slapping against the surface, breathe in the fresh air and city odors, and feel the wind against your face.

Past lives and experiences involved these same smells and sounds. You can feel those who walked and lived along the waterfront. The remnants of a waterfront far different than today haunt the ominous space taking up this structure.

“Day’s End” is a permanent work of public art commissioned by The Whitney Museum of American Art. Hammons is a pioneer in the art world, an elusive shapeshifter. He challenges the notion of the artist and the value of art through his works created in New York City and Los Angeles during the 1970s and 1980s. But despite his credibility, he never conforms to the art world’s elitist rules, refusing exhibition offers and selling his work himself rather than through a gallery.

Hammons’ work is so mysterious because it’s often unexplained. In a 1986 interview with art historian Kellie Jones, when asked if the context of his work was political, Hammons said, “I don’t know. I don’t know what my work is. I have to wait and hear that from someone.”

Reactions and discourse from the public are what makes Hammons the artist he is today. While he works in a variety of mediums, there is always an engagement with identity, politics, race, and culture. One of his most notable works “Pissed Off” consists of photographs of him urinating on Richard Serra’s public sculpture “T.W.U.” Another work of his, “African American Flag,” reimagines the American flag with stripes and stars in the colors of red, black, and green.

Without knowing the context of “Day’s End,” it seems different compared to Hammons’ other works. But the work is inspired by and takes the name of Gordon Matta-Clark’s “Day’s End.” Matta-Clark’s version from 1975 involved holes being cut into a shed on a now-demolished Pier 52 where Hammons skeleton-like structure now stands.

There’s a neglected history that haunts the remains of Hammons’ tall steel poles where Matta-Clark’s once stood. It contains a long-lost culture; it represents a lively queer scene and art period from the late 1970s and early 1980s.

New York City’s piers are historically queer. Most LGBTQ+ people during the 1970s sought these largely abandoned piers to meet one another. The waterfront became a space for isolation and shelter, but most importantly, community. While it was widely known as a cruising spot during the evening, the day was just as popular for sunbathing along the same waters that clash against the Gansevoort Peninsula.

In the early 1980s, these abandoned buildings attracted artists such as Matta-Clark, Alvin Baltrop, David Wojnarowicz, Peter Hujar, Keith Haring, and many more underrated but groundbreaking artists. A rich history, community, and art scene thrived in these vast empty spaces that served as their studios. “This is the real MoMA,” Wojnarowicz stated about the art scene along the water at the time.

But there was also a dark side to the piers. Violence and death occurred on the same walking grounds, seeping into the same waters that have stirred for centuries. Trying to put together a history and community from nearly fifty years ago is difficult when the many lives of that era were taken too soon by the HIV/AIDS epidemic. It seems unimaginable that this era existed in an area that has transformed into one of the most exclusive and wealthiest neighborhoods in Manhattan.

Hammons has managed to create something that disguises the sleekness of Hudson River Park. These tall steel structures oddly mimic the boxy, “new,” and “trendy” architecture often associated with gentrification. You may interpret that Hammons does this for a reason — to symbolize a gritty and erotic past through a changing landscape. The tall, steel structures loom over the water, but the old history remains in this haunting space.

So when you’re feeling burnout, step away from your work and go on that walk away from campus. Distance yourself from the building and allow your mind to wander, really engage with what’s around you. Practice close looking, where you examine all the details in a work of art. Question things that you may not understand at first glance. Wonder why the artist made these choices, and think of the context of a single detail you might regularly overlook.

Sit in that beach chair at Gansevoort Peninsula. While you take a break from schoolwork, you can draw inspiration from the things surrounding you. Whether it be the rotten smell of the Hudson or the deeply rooted history fossilized in “Day’s End,” all are worthy materials of something that may help you in your studies and future projects. You may find that you can still learn a thing or two by distancing yourself from campus.

Or maybe you don’t have to take anything educational from this experience. Sit by the water and reflect — let your thoughts run wild and imagine the excitement of forbidden lovers enveloped by darkness. Reflect on what made the darkness and isolation so comforting to them and why that may comfort you.

The days of cruising and cutting holes into abandoned sheds may have ended along Hudson River Park, but the pier remains.