Well-behaved women rarely make history, but they do get DIOR sponsorships.

The New Museum is now displaying “Judy Chicago: Herstory,” an exhibition that spans the sixty-year career of acclaimed feminist artist Judy Chicago. The exhibition, sponsored by Dior, occupies four floors and showcases paintings, installations, sculptures, photography, textiles, embroidery, drawings, and printmaking. It also features “The City of Ladies,” a sort of exhibit within the exhibit that showcases female artists that influenced Chicago’s work.

While the exhibit demonstrates the many dimensions of Chicago’s career, some of its feminist ambitions fall flat. The prominence of the exhibit’s’ sponsorship dulls the impact of its political messages. Though the use of “Herstory” in the exhibit’s title may cause an instinctively adverse reaction, in some ways, the name is apt. Some of the recurrent themes in Chicago’s art, such as an emphasis on equating anatomy with female experience and struggle, feel stuck in the 1960s, second wave feminist movement.

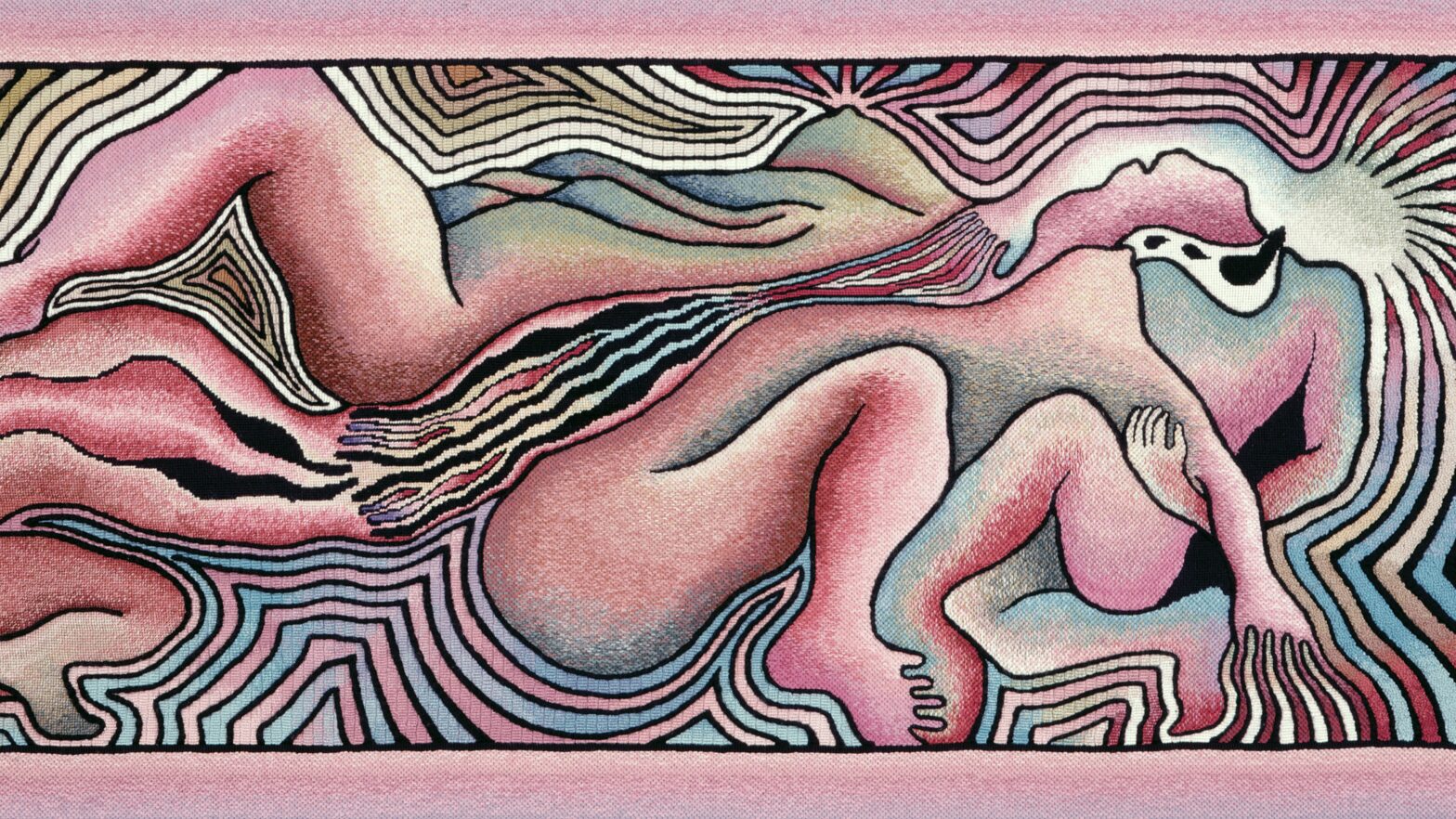

Judy Chicago, or Judith Sylvia Cohen, was born in 1939. In 1963, she underwent another name change and made a statement by shedding her married name, Gerowitz, and took the name Chicago as a homage to her birthplace, independence, and identity as a woman and artist. Chicago began explicitly aligning herself with the Women’s Liberation Movement in the 1970s — known for her use of collaboration, working in traditionally feminine and less respected mediums like textiles and the plentiful vaginal and phallic images that populate her pieces.

The “Great Ladies Series” on the first floor of the exhibition illustrates Chicago’s style at its best. Using sprayed acrylic on canvas, these paintings are full of smooth, blended pastel colors that resemble psychedelic sunsets and are named after historical female figures. In the 1960s, Chicago attended auto body school and acquired many skills, including spray painting, in a male-dominated environment. The paintings “Queen Victoria” and “Christina of Sweden” were later transformed into limited edition DIOR handbags that retailed for $8,500.

One of the most novel and exciting aspects of the exhibition is “The City of Ladies.” Chicago assisted in curating works of female artists from the cannon that influenced her. “The City of Ladies” seeks to make space for female artists from history. The exhibition-within-the-exhibition includes paintings from the likes of Hilma af Clint, Frida Khalo, and Leonora Carrington. There are video installations of Martha Graham performing “Lamentation” and Maya Derhen’s short film “Meshes of the Afternoon.” There are even poems by Emily Dickinson scribbled on scraps of envelopes. The room, designed by Chicago, features bright, butter-yellow walls and a deep purple floral carpet. Banners from another project, “What if Women Ruled the World?” hang from high ceilings.

The banners bearing Chicago’s questions about a world ruled by women adorned the runway in the DIOR haute couture Spring-Summer 2020 show before they graced “The City of Ladies.” Some of Chicago’s follow-up questions to “What if Women Ruled the World?” were “Would there be equal parenting?”, “Would there be violence?”, and “Would buildings resemble wombs?” The project’s website describes the banners “which were created in collaboration with Maria Grazia Chiuri of DIOR, as the impetus for a new revolutionary call-and-response to invite allies all around the world to share ideas and create a global community supporting gender rights.” It is hard to imagine how a collaboration with a luxury brand could be the impetus for anything revolutionary when the goals of capitalism and feminist liberation movements have so often been at odds.

Chicago asked for participants’ opinions on the series of questions embroidered onto banners. Online responses were “digitally threaded” into a quilt. A physical representation of the quilt is on display on the seventh floor of the New Museum, and visitors are invited to add their own responses. The scope of this collaboration is impressive, but the sponsorship makes it feel less sincere.

Some of the questions are inherently leading, like “Would both men and women be strong?” and “Would both men and women be gentle?” — implying that Chicago believes men and women are fundamentally different. The question “Would there be private property?” seems in poor taste for a project in collaboration with a designer brand like DIOR.

Criticism of Chicago comes from a place of understanding what she’s capable of. The political messages in newer projects like “What if Women Ruled the World?” are far more present and powerful in an older project “Womanhouse.” Chicago, fellow artist Mirium Shapiro, and about 20 students from the Feminist Art Program at California Institute of Arts transformed an abandoned mansion into an artist collective dedicated to exploring women’s experiences and the domestic sphere. “Womanhouse” is the project in this exhibition that comes closest to a depiction of a utopian feminist past. “Womanhouse” wasn’t catering to brands or art institutions. It was just about creating a place for women.

The exhibition’s title “Judy Chicago: Herstory” describes both the survey of Chicago’s work and her role in conversation with the female artistic cannon, but it doesn’t do her work justice. It’s a little cheesy and passé; it conjures to mind pink pussy hats, “this is what a feminist looks like” t-shirts, and even Rupaul’s Drag Race lingo. The word “herstory” is a relic of the girlboss era. Girlboss feminism is more a neoliberal marketing campaign than a movement. Rather than collective liberation, it is more concerned with personal choices. It proposes women can gain equality by reaching elevated positions within existing oppressive systems. It brings feminism into the mainstream but at the cost of co-opting it. It turns it into a buzzword for brands like DIOR to use in the “mission” tabs of their websites. Chicago has been aligning herself with feminist causes throughout her sixty-year career. It seems DIOR just wants to cash in on being seen as a politically conscious brand because that’s what sells right now. Ultimately, the exhibition demonstrates the challenges artists face when they endeavor to make a living without comprising the messages in their art.

“Judy Chicago: Herstory” will be on display at the New Museum until March 3, 2024.