An intimate photo exploration of queerness and race comes to Soho

Located on 26 Wooster Street in SoHo lies the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art. The museum has stood the test of time, displaying the works of LGBTQIA+ artists and communities since 1987. On Friday, Sep. 22, the museum opened its doors to display the works of Christian Walker in his first exhibition, “Christian Walker: The Profane and the Poignant,” until Jan. 7, 2024.

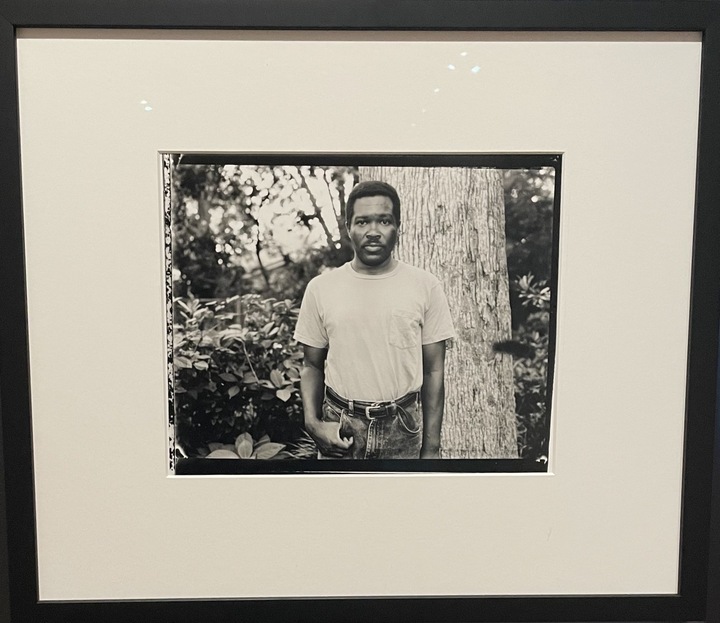

Walker was one of the earliest-known Black gay critics, curators, and photographers active in Boston, Atlanta, and Seattle from the mid-1970s to the mid-1990s. He examines the intersections of queerness and race in America through his photographs, writings, and curatorial projects.

The museum is small and consists of only two galleries but is well worth the visit. Upon entry, the viewer is taken back in time, greeted by black-and white-portraits of people Walker encountered in Boston during the late 1970s. The exhibition delves into Walker’s decades spent in Boston and Atlanta. Framed photographs are accompanied by tables decorated with articles and publications that contextualize each time period.

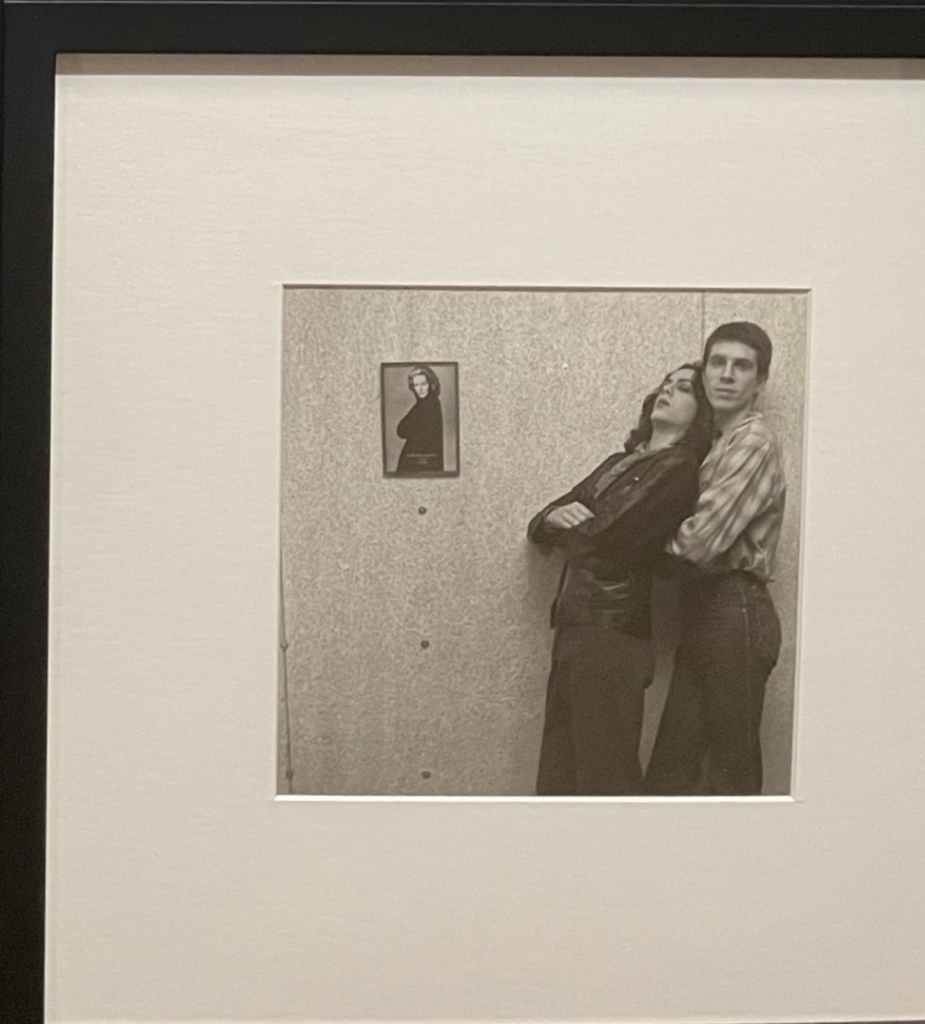

His brother and niece sit on a leather chair in a living room; a resident from a group home floats in a swimming pool; two people tenderly embrace in front of a framed picture of Betty Bacall. The subject’s eyes stare beyond the lens, breaking the fourth wall between the observer and those being observed. Within the quick shutter of a camera, the viewer is immersed in a moment in time: a community that once existed but has now disappeared.

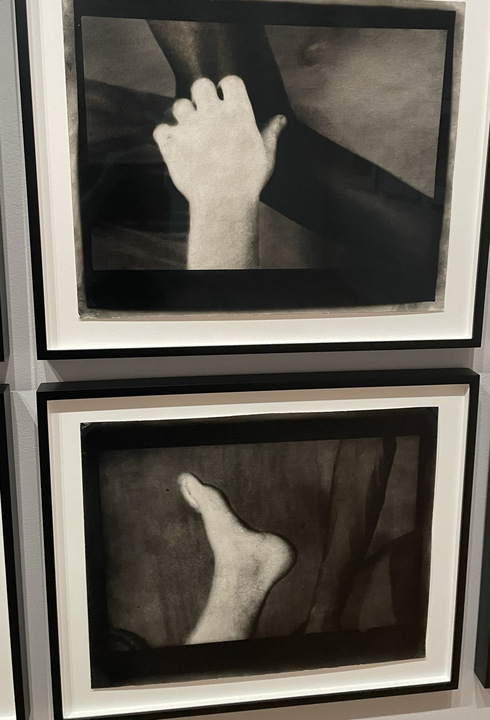

Walker captures intimacy. Whether it’s the people he encountered or the places he went, his experience as a Black queer artist reflects in everything featured in the exhibit. In his earlier photographs that capture loved ones or later works like his “Miscegenation” series that depict his body entangled with white men’s bodies in oil paint, Walker examines the role of the body in a space. Depicting the action of being physical with another person, examines his position as a Black queer man in a white cis-heteronormative society.

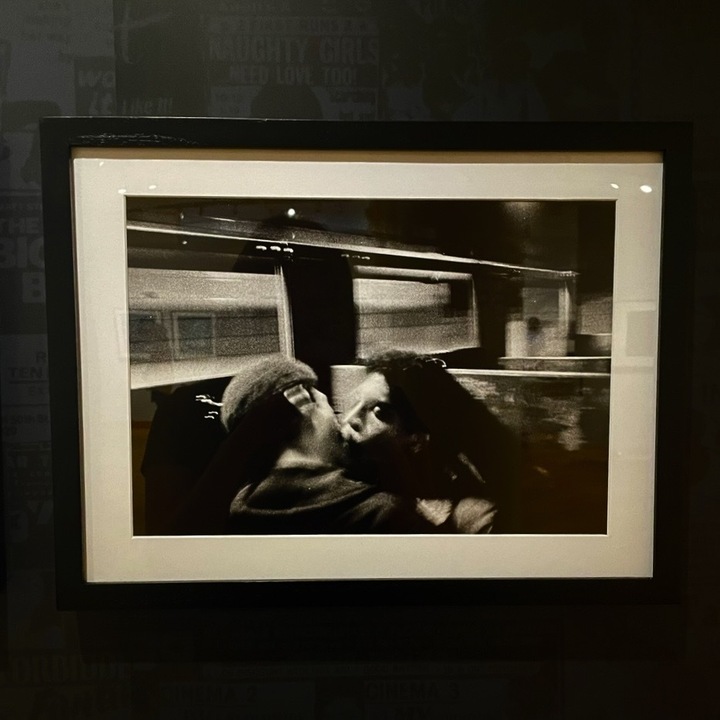

The museum has selected work from one of Walker’s most famous projects “The Theater Project,” a photography book documenting an adult theater in Boston during the 1980s. Grainy, blurry, black-and-white photographs depicting life inside the theater capture a sexual culture that was being erased by mass campaigns against gay men in the 1980s. The final image of the book captures a heated kiss between two Black men in a bathroom stall. The image is a force, encapsulating a space where gay liberation could thrive between movie theater screens and padded theater seats — away from the loudness of misinformation and stigmatization.

“The Theater Project” caught the attention of Boston Licensing Commissioner Joanne Prevost Anzalone, who used the book as evidence to order the theater to be shut down temporarily. Walker’s response can be viewed on one of the tables, in an original copy of “Gay Community News” where he said “It’s a very outrageous situation that a document, a piece of art, is used as a way of harassing men…”

While this is the first and most in-depth solo exhibition dedicated to Walker, there are inconsistencies and gaps because a majority of Walker’s work has been lost. After his death in 2003, his residence made no effort to contact his boyfriend or brother. This caused the majority of his photographs and belongings to remain unclaimed.

In this well-curated exhibition, the museum honors him and his transformative works as best it can. Walker is one of many Black queer artists that have been erased from the artworld, a pattern entangled in the queer history he attempted to preserve.

Though the spaces captured through images and writings have vanished, they remain powerful as ever in the works the museum has been able to recover through friends, family, and anyone involved in Walker’s life no matter how big or small.

The viewer follows Walker’s camera and words through a labyrinth of his mind and lived experiences. A wall of the exhibition quotes the path-making individual, reading, “It is the artists committed to the radical restructuring of subjectivity who are pioneering the visual imaging of future culture.”

The future cannot move forward without knowing the past. Historically, the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art has been a space where preservation can converse with a history of violence and oppression that has targeted LGBTQIA+ people. “The Museum of Art is committed to preserving, diversifying, and making accessible the artworks in its collections, as well as to the representation of an evolving constellation of queer experience,” they said in their mission statement.

The photographed kiss between the two men in the bathroom stall will never happen again. But decades later, long after Walker has almost been forgotten, the kiss lives on the walls of the museum.