In preparation for their thesis projects, Senior Communication Design (CD) students at Parsons School of Design spend six-hour-long classes poring over resources, collecting images, making books, and designing websites to stir inspiration. Finding a focus for their projects often entails reflecting on personal histories — but students express that the lack of representational, ideological, and cultural diversity among faculty has made this difficult.

While associate directors of the CD department, Kelly Walters and Elaine Lopez, are both women of color, the Black and Latinx cultures they represent are still minorities within the faculty of the department. “Considering the state of arts education in general, I know that there’s certain courses that over index in white male representation, especially when it comes to coding or programming. And that’s indicative of the issues in the industry at large,” Lopez said.

“Design historically was a field practiced by white males. And there’s really not anything we can do to change that. I think it requires bringing in faculty with those lived experiences that are going to just bring that perspective in to be able to pivot and change the industry,” Lopez said.

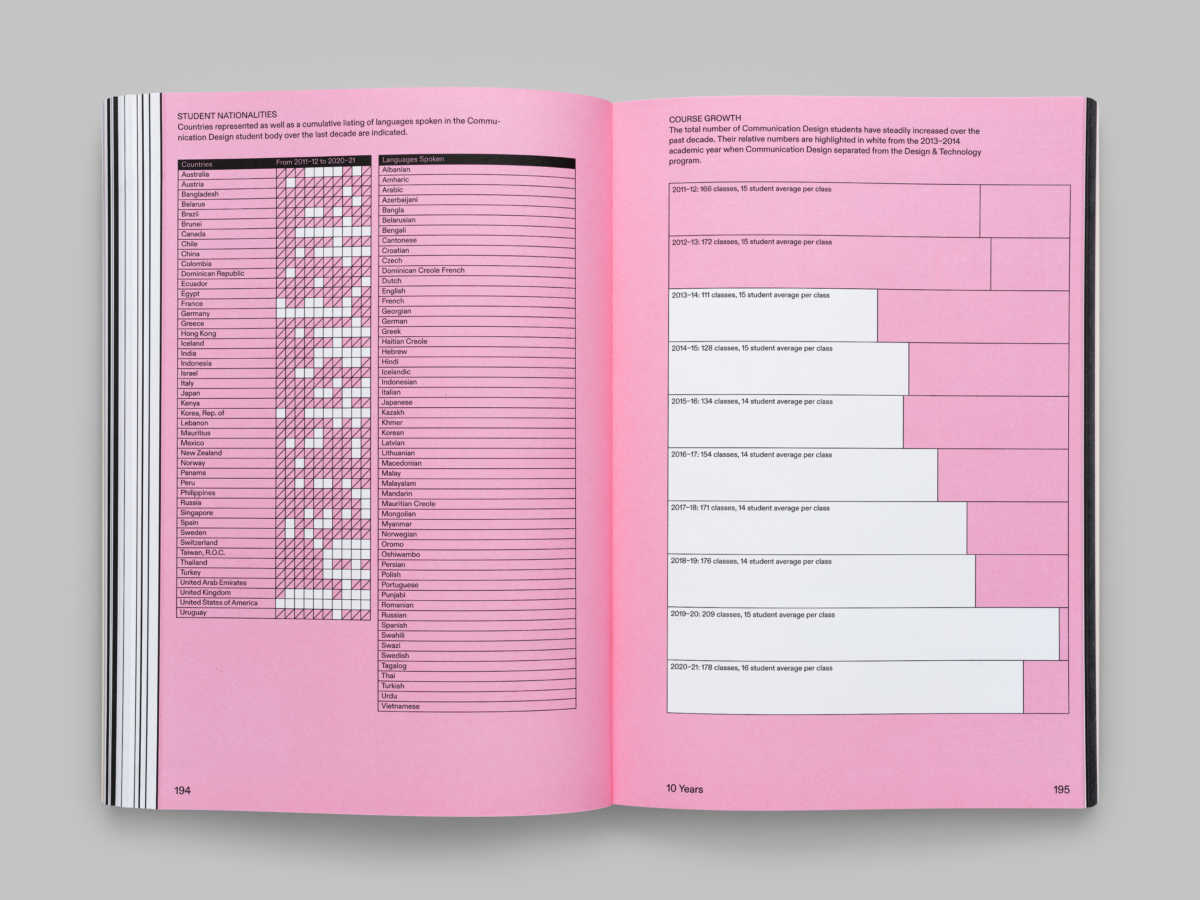

From 2011 to 2021, only ten percent of the 424 faculty members who taught in the departments had degrees from universities outside the US. Though Walters and Lopez’s individual practices may work to combat the oversaturation of western perspectives in design, when it comes to integrating these ideas into the department, students feel that the lack of ideological diversity among CD faculty still stands in the way. “A lot of professors come from prestigious universities, master’s programs and such. Even at a very basic level, there’s an overlap of cultural references that tend to get repeated over and over again,” said Shravani Bagawde, a thesis student in the CD program.

When opportunities arise to tap into diverse perspectives, faculty still fall short. The curriculum of the Communication Design program — as with most other art and design concentrations — reflects a westernized understanding of design. “In graphic design there’s this prevailing idea that good design is Swiss design, or European design. And our curriculum, at least right now, is very much reacting to that,” Bagawde said, “but I also think even the way that critique is approached, still comes from a pretty unified place. Growing up in a western society, for me it’s always been easier to grasp those things. So I think about people from outside of that, for that matter, there’s that dissonance,” Bagawde said.

In the Communication Design Department at Parsons, at least 45 nationalities were represented and 54 languages were spoken among students from 2011 to 2021. International students are forced to cope with a gap in understanding due to underrepresentation in curriculum and faculty, while the remainder of students are kept in an echo chamber of ideas, methods, and references that draw from the American design canon.

“Even the books we read didn’t really resonate with me culture wise,” said Sofia Cacho Sousa, a 2023 CD graduate. Sousa was born and raised in Peru, and shared her experience completing her thesis project centered around an art movement in her home country. “In my case, when I talked to my professor, he did give feedback about [my thesis], but it was more design oriented,” Sousa said. “I guess he didn’t have enough knowledge about my topic to fully understand and be able to help me in a detailed or extensive way in my area of interest.”

Other students speak to alternate ways cultural representation is being avoided in the classroom. “It seems that when students come up with a project that focuses on culture or identity, it’s a free pass in a way where it doesn’t open a lot of room to critique one’s work,” Kiara Putrilia, another senior in the CD department, said. “It makes me not want to make a work talking about my own culture. Just because I feel like you just don’t really get fair criticism because it’s a very sensitive thing.”

Professors also contribute to this type of classroom environment. “I think teachers assume that role as well, where I can tell that they’re not really going to delve into your work if it has cultural ties,” Putrilia said. This apprehensiveness towards critiquing unfamiliar cultures is a barricade between the status quo and the need for change, resulting in a limbo where students are unable to receive comprehensive feedback on their work and their opportunity for growth is reduced.

“How am I supposed to critique colonialism through design, if I’m doing it through a system that is entirely built in it?” Bagawde said, feeling the impact of this stalemate on her educational experience.

There are positive contributions being made by departmental faculty to undo this systemic harm. Lopez mentioned that Walters and herself came to Parsons from a fellowship program sponsored by a consortium called the Association of Independent Colleges of Art and Design (AICAD). The program works directly to help increase faculty diversity in art and design institutions, by giving MFA graduates of different cultural backgrounds the opportunity to be placed at a design institution as a full time professor. “I don’t actually know of any other Design programs that are led by two women of color. So that’s also super unique and exciting.” CD department director Lopez said in regards to her and Walter’s position in the department.

While these endeavors mark significant progress, professors are still working within the limitations of systemic prejudices in the design industry. “It’s a challenge and a delicate balance to teach people what they need to know so they’re able to enter the industry and work within the constraints that are there because whether or not industry has diversified — that’s like the whole problem,” Lopez said.

As students continue to feel the impacts of a lack of ideological and cultural diversity in the program, the way forward could be in listening to their experiences and further input. “I’m interested in seeing how the educational process can be more democratic in a way,” Bagawde said.