Content Warning: This story discusses depression and suicide. If you or a loved one struggle with this, please contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255.

The days leading up to my brother’s death, he didn’t eat anything and almost never left his room. He hadn’t been talking to any of his friends. It should have been a sign that something was wrong, but I didn’t see it.

My brother died by suicide on the Fourth of July. He was 22 years old.

He and I had always been different and he had been shutting me out since we were teens. I wanted to be closer to him, but I was always met with a brick wall. I wonder every day if I had tried harder, would it have made a difference? Or is this the ending that was always going to happen? I’m not sure which is worse.

The truth is that I had no idea my brother was depressed, or at least not that he was suicidal. I’m not sure how much of an impact the pandemic had on his mental health, but I know he had lost the structure of his school life and his ability to do things he liked, like going to the gym or seeing his friends.

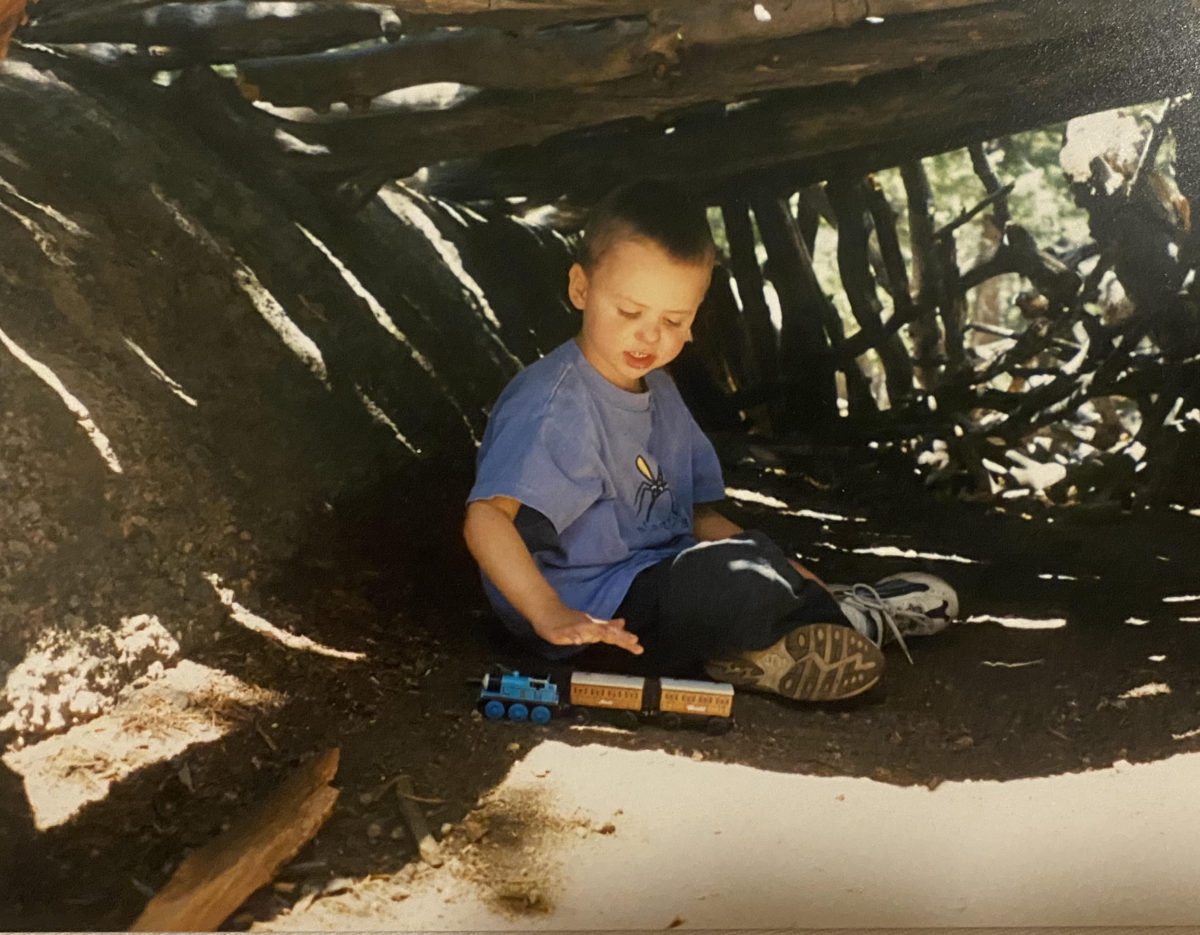

My brother would always take the bugs in my room outside, no matter what time it was. He let me drag him to the Glee movie when I was 11, even though I know he hated it. He always gave our dog the longest walks. He kept games on his phone so our little cousins could play them. He loved sports, especially football. He wrote for his college’s newspaper, just like me. These are the ways I try to remember him.

The night he died I couldn’t sleep, so I spoke to my aunt on the phone for hours. She told me about how her brother had also died by suicide; a bond she and I will always have. I looked at the light on my ceiling and wondered how I was going to live with this.

In The Chronology of Water, Lidia Yuknavitch wrote, “I’m not sure it is possible to articulate grief through language. You can say, I was so sad I thought my bones would collapse. I thought I would die.”

For the following days I didn’t even feel alive; I felt like I was existing outside of my body and my life. I didn’t eat because it felt disrespectful to my brother. He wasn’t eating and he never would again.

I still have a hard time processing the reality that he will never be doing anything ever again. Over the summer, with both of us at home and our dad at work, I would hear him doing things throughout the day, like walking the dog or playing a video game. After he died, I would sit in my room and wonder what he was doing, until I realized he wasn’t doing anything anymore. That realization comes everyday and it hurts just the same.

I could not kill any of the bugs that appeared in my room after he died because I was afraid they were him, coming to visit me. The day after my brother died, I stared at a beetle on my bathroom wall and cried.

Weeks after he died, I still found myself struggling to do normal things. I used to floss my teeth everyday, and for months afterward I just couldn’t bring myself to care. What did it matter anymore?

I would sit on the floor of his bedroom, going through every video game and movie he owned. I looked through his closet to find something of his for me to wear. I picked a navy blue sweatshirt, something that he had worn constantly. He never would have let me wear it when he was alive. He never cared much for fashion, and for years he pretty much only wore sweatshirts and cargo pants. I look everywhere now for green clothing because it was his favorite color.

The pandemic made me feel so lonely in my grieving, and grief is already incredibly isolating. There weren’t many places for me to go, so I had no choice but to wander around the house where my brother died. It felt like I was suffocating in my grief.

I carry my grief with me everywhere I go; to the grocery store at 5pm and to this newsroom every Zoom class. It lives in me and for a while I felt like I was more grief than I was a person.

I planned a large part of his funeral. I was in charge of making a slideshow, creating a playlist, and helping my aunt write his eulogy. I worked desperately to find his Spotify account so I could make sure I picked songs I knew he liked. Although, I did sneak in multiple Glee songs, just so I could annoy him after death. I didn’t speak because I knew I wouldn’t be able to. I still struggle to talk about him without crying. I wonder if, or when, that will ever be something I’m able to do.

I’ve heard that people dealing with grief will shut others out. I tried to do the opposite of that, even though it was hard. I felt lonely, but I didn’t have to be alone. This is the most I’ve ever allowed myself to depend on others. I asked my friend Izze to hold my hand at his funeral; something I would never normally ask. I told everyone around me the truth: that I didn’t know how I was going to deal with this.

I have posted a lot about my brother on social media, I think for the same reason I’m writing this: to put my pain somewhere else. I’m allowing it to live outside of my brain, so I don’t have to carry it alone.

I have found a lot of solace in media about grief. The only book I could physically make myself read after he died was Diana Khoi Nguyen’s “Ghost Of,” a poetry book about her brother’s suicide. Sometimes I will clutch that book against my chest, like a hug. I had actually read it for a class months before the pandemic even happened. It’s strange how connected to the author I ended up feeling. This semester has been hard for me. I’ve had to turn off my camera in Zoom class because I was crying, just because something reminded me of my brother. I miss him every single day. I still text him, knowing he will never read the messages.

I didn’t disclose my loss to any of my professors, I think because I fear it would make me look less professional. I’m afraid of being looked down upon as weak or unreliable. I still want to be me. At the same time, I also don’t want to deny or avoid what happened to my brother. I don’t want him to feel that I’m ashamed of him or the way he died.

I feel obligated to say something about preventing suicide or how to help others deal with depression, but the truth is that I don’t really know. I wish that just being there for someone when they’re depressed was enough, but sometimes it’s not. I’m not sure what is, but I think allowing people the space to really discuss how they feel, especially for men that are depressed, is a start. I wish my brother felt like he could have told people how he was feeling. I wish he would have let people in.

I am trying everyday to do better. I am back to flossing my teeth everyday. I want to feel happy to be alive rather than guilty that my brother isn’t. I carry him with me everywhere, and maybe that’s enough.

If you or a loved one struggle with depression or suicidal thoughts, please contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255.