This article appears in our November print issue. You can pick up a copy on newsstands around campus, or at our newsroom in room 520 in the University Center.

David Van Zandt started as president in 2011, serving as The New School’s eighth president, after Senator Bob Kerrey. The university was scattered around Manhattan when he came into office, with Mannes School of Music on 80th Street, Parsons in the Garment District on 40th Street, and the School of Drama on the west side, on Bank Street. He will step down near the end of this academic year, and Dr. Dwight A. McBride will begin his term as president in April 2020. McBride is currently provost and executive vice president of academic affairs at Emory University.

In the last 30 to 40 years, it seems that college has become less about getting a classic liberal arts experience and more about being prepared to enter the workforce. Where does The New School stand in that conversation? Where should it stand?

When I went to college, I had a standard liberal arts kind of education — we didn’t even think about jobs. We just sort of expected we’d come out and we’d do something. [Today] you need to be able to communicate in a way that a liberal arts education does, you need to have an understanding of human beings. One thing for all our students would be not only to have that great Lang education, but also a particular technological skill set, whether it’s web design or it’s some kind of coding, because that’s what gets you your first job. Over your career, it’s going to change dramatically. The world is going to change. Technology is going to be different.

The New School has a great advantage over a traditional liberal arts college, because, in a traditional liberal arts college, you only get the first part. It’s almost a neurological bias against the second part, and you’ll talk to faculty at some of the great liberal arts colleges and they’re appalled by the idea that students think so much about jobs — but they come from my generation when they didn’t have to worry about that. In an art and design school you’re basically learning a lot of technical skills, but your liberal arts training is anemic. The people who go to conservatories, music conservatories, arts and design schools — their liberal arts are music history, art history, you know, five times over. They don’t do social sciences, and they don’t do broader literature kinds of things the way we can here at The New School. It has to be that mix, and I think we’re in a great position to deliver that to students.

How do you see the role of president of The New School?

Different presidents are going to see their role differently. Very traditional presidents — again, this is a generational thing — were really just about keeping the faculty happy, keeping the students from boiling over, and raising money. I think, today, it’s a far more difficult job, and I sort of view it as basically setting the direction of the university, working with people, and then pushing the institution as much as you can. That means caring about every little last bit of [the institution], from the admissions process, to how students are served, to even the facilities. I walk around [school] picking up stuff because I think I need to have (as much as possible) an attractive looking place, but at the end of the day it’s about the direction of the university, and it goes back to what is going to advance your students’ futures.

What are you the proudest of, looking back on your time here?

In today’s world, you’ve got to be broadly educated. To have a competitive edge, whether you’re a Parsons student or a Lang student or a CoPA student. Because just being a straight liberal arts student is different today, just being a straight art and design student or a performing arts student… it’s a different world. We probably couldn’t have done that unless we put the campus together physically. Moving fashion down from 40th street was a big deal. Moving Mannes down was gigantic. The University Center, which was built during this time, was spectacular.

The other thing I think, if I look back, is really focusing on the kind of student we have here. I think it was always kind of implicit but we began to more aggressively try to recruit students of a particular kind. Whether you’re at Lang or Parsons or CoPA, the group of students we get here are very creative people.

They’re very socially engaged because they want to do something with that creativity. They’re coming here, whether they know it or not, to develop that creativity so they can actually have an impact on the world. We get some people who want to either play well or draw pretty things, but I think most students have a social mission behind how they use their talents.

With that social justice focus in mind, what do you think about The New School’s history of student mobilizations and various occupations? What do you think it says about the type of student here?

I think it reflects what The New School is, why people come here, and who the people are who do come here. I describe them as creative people who use that creativity to make a difference — to be socially engaged. That’s exactly what you would expect. There is a balance there, trying to be sure one doesn’t overtake another. But to me, that’s all part and parcel of what this place is about. You can go to another institution where the students all want to be fine artists and want to sit in their studios, which is perfectly fine. But that’s not what our students are about, or what the institution has ever been about.

How do you feel about students targeting you in protests?

That’s part of the job. I’m not sure it’s the best thing for an individual student to have that kind of anger, but I recognize people do, and you’re probably going to get more of that at The New School than you may at some other place.

With youth, there’s more of an urgency to get going — you see what’s wrong in the world around you, and you want to push very hard to try to do something about that. Sometimes, it gets pretty extreme.

What are the biggest news events of your presidency?

Well, Occupy Wall Street. I think The New School in particular was impacted by that. One major reason was just where we were — close to Union Square. People came marching down 16th Street, turned down Fifth Avenue, and decided it would be a great idea to occupy our student center, which we had to deal with for over a week. [During] Hurricane Sandy the following year, all the lights and electricity below 34th Street were knocked out in the city for a week. We did have a generator in the Arnhold Hall building, so we put a lot of students there, mostly New School, but some from NYU and others, and that was sort of a challenge. Lastly, probably the biggest event was Trump’s election, because that’s had such an impact on the way people feel and what they think and how they talk. I think that’s something, and I don’t think we’re alone in that. It’s something that’s impacted all of New York City, all or most universities around the country, and people all over the country, often in different ways.

2020 presidential candidates Senator Bernie Sanders and Senator Elizabeth Warren have proposed forgiving all student loan debt. What are your thoughts on those proposals?

I think they’re well meaning, but I very much fear it’s just replicating inequalities in society. The kinds of stuff that Sanders or Warren or some other candidates are talking about is across the board. It’s either forgiving the debt of even wealthy people, or providing free tuition to wealthy people. First of all, I don’t like the inequality of it. I think it ought to be, at least, means-tested. The second thing is, we have to realize, a part of the cost of going to university, particularly in New York City, is the living expenses. It’s so much bigger than just tuition. If you don’t cover [student] living expenses or help them, it’s not a viable option.

How do you see The New School moving forward?

We have to figure out how to make it accessible, because we’re getting to the point where, in terms of costs, it’s becoming more and more prohibitive. So I think that’s going to be the biggest challenge for the next president and for presidents down the road. I wish I had an easy answer to that.

It’s also got to play to its strengths. It’s all in the students, it’s in creativity and social engagement. Those are the two things — the kind of student we get here, that makes this a different place than NYU, a small liberal arts college someplace, or even RISD or Eastman School of Music. It’s the nature of the student we have here. We have to play to that strength and keep getting those people, not trying to be plain vanilla or trying to be like everybody else. If you try to be like everybody else, in today’s world, you’re lost. You’re lost.

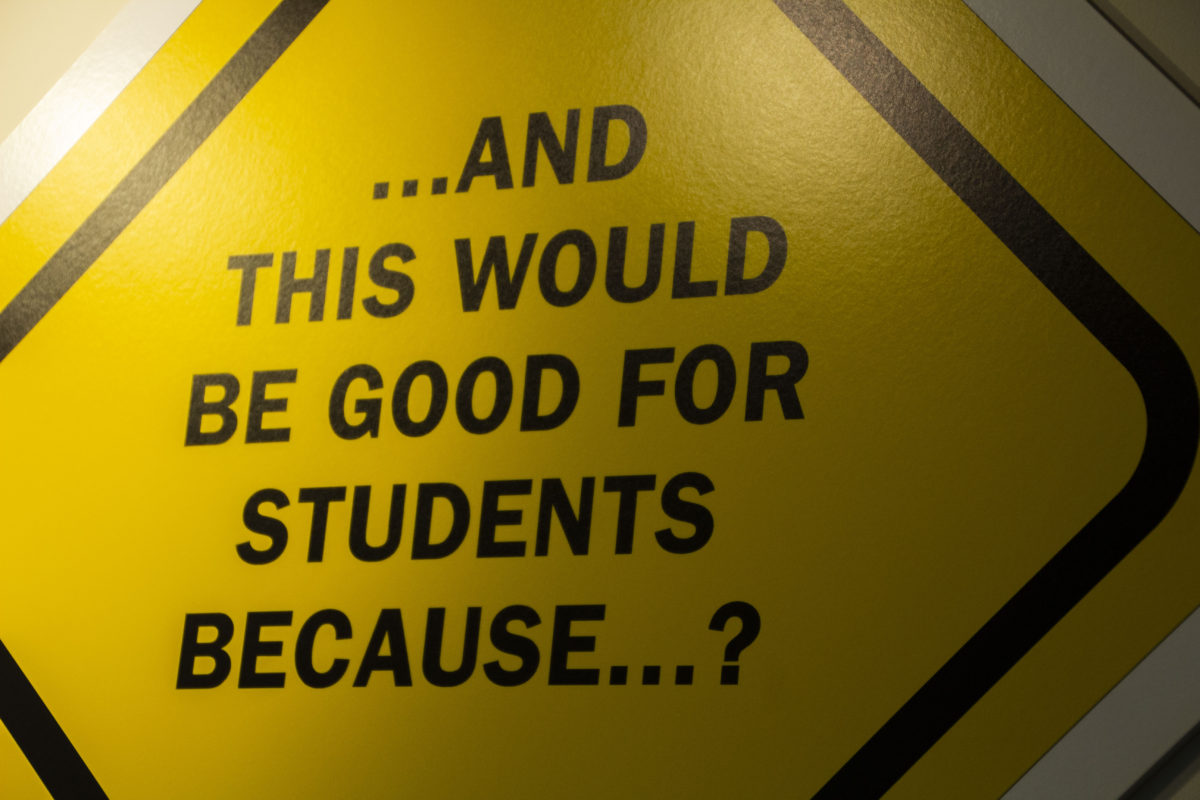

What advice would you give to the future president of The New School?

Well I think you’re sort of staring at it right there*. It’s very common in the university world for people to not be focused on that, to be be more worried about research. But the reality here is: What are we here for? If you read our mission statement, it’s all about preparing students. It’s not about having great faculty or having nice facilities, it’s all about the students. I think any president in the future has to focus on: Why is this good for students?

*Refer to image

How have you grown in your ten years as president of The New School?

I’ve learned a lot more about higher education, certainly. I’ve learned a lot about art and design, which I didn’t know before. I had a very abstract view — I knew liberal arts, because I’d sort of grown up in that kind of culture. It’s the first time in years that I had dealt with undergraduate students, because I was always dealing with graduate students for most of my career.

You said you won’t give a speech at graduation because it should be focused entirely on the students. If you were to say something to students as a parting message, what would you say?

You’re living in a very difficult time, but you’re also living in a time of probably far more opportunity than anybody else, particularly if you do have a good education. Take advantage of that. Don’t lock yourself into one particular thing — be very flexible, your career will be much better if you do a bunch of different things. Follow that passion, that project, which is being very creative and wanting to be socially engaged. If you continue that sort of theme through your life, you’ll have a very satisfying life. And the last thing I would say is stay connected with people you meet here. I still go out places with my college friends, in a way I don’t necessarily with friends that I met in different stages of life. It’s very important.

What will you miss about The New School?

[I’ll miss] being around the energy of the place and the students. I think I’m going to look back and say I didn’t spend enough time sort of just bathing in that, sitting in the middle of the University Center, or something like that. That’s probably what I’m going to miss the most — day to day activity. I’ll be able to live a little bit through my wife because she’s going to keep teaching at Lang as long as Lang will have her. We’re going to live in the city, and I can’t come around too much because I don’t want to get in Dwight’s way, but I certainly will be around.