A previous version of this piece used the term “alumni” in the subhead to refer to notable people who came through The New School. We have changed our language to be more specific.

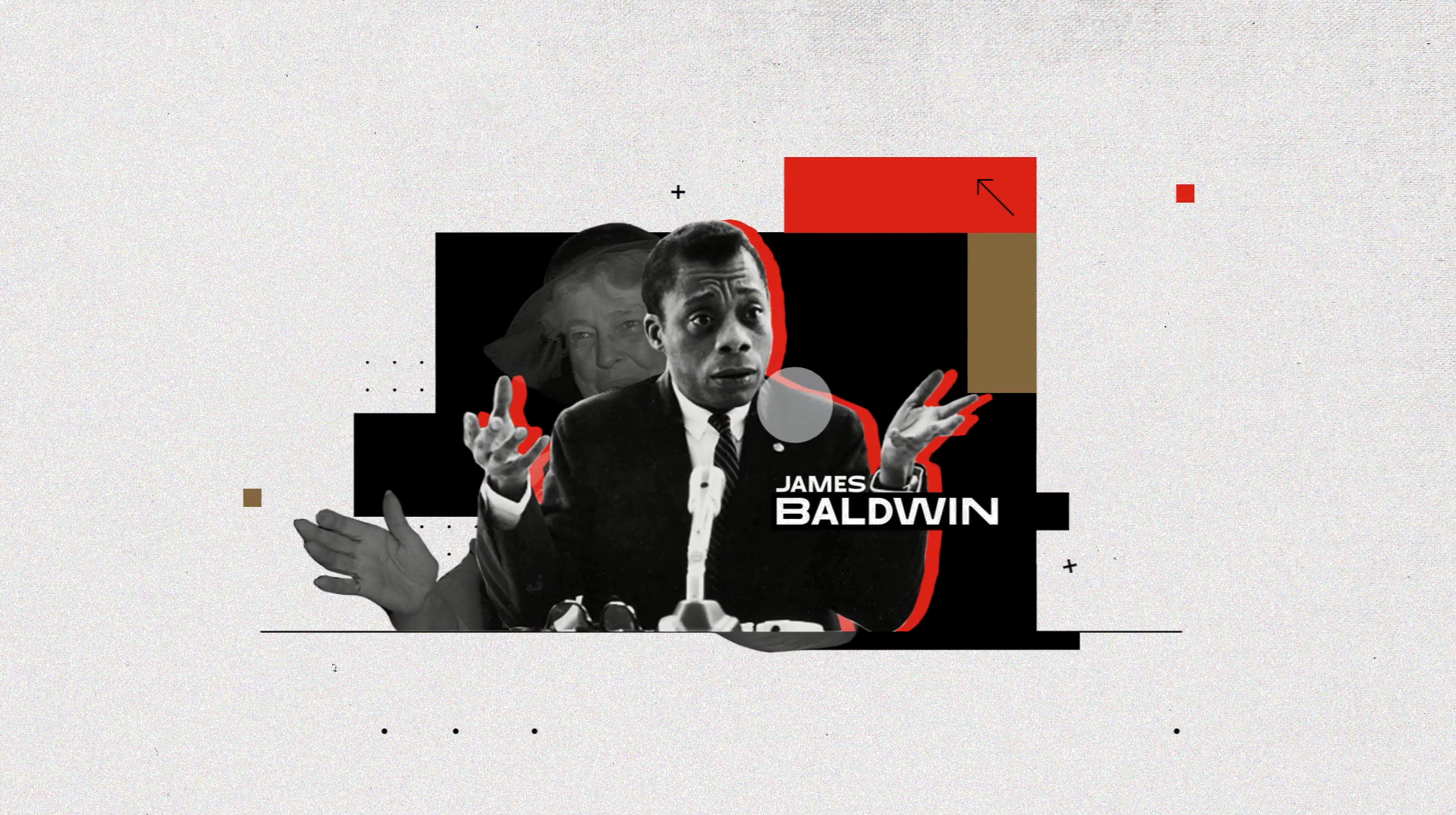

About halfway through The New School’s “100 Years of New” video, produced among other articles of fanfare for the university’s centennial celebration, James Baldwin’s name and portrait flash on-screen. As his image appears, the narrator describes New School students as “groundbreakers” who “create the movements that forever change the world.”

Baldwin certainly fits the description: a prolific writer and activist who became a prominent name in the civil rights movement. But was he a New School student? How much time does a person need to have spent at The New School in order to be celebrated as an alum?

“All of the individuals featured in the video have a direct connection to The New School and illustrate different aspects of our proud legacy,” Ashley Bruni, the university’s Director of Brand Strategy and Activation, wrote in a statement to the Free Press.

Still, using Baldwin and the 22 other figures from The New School’s past in the video raises questions about the best way to convey the school’s complex narrative.

What does it take to be a New School alum?

“Everybody wants to be connected to James Baldwin in 2019,” said Mark Larrimore, a Lang religious studies professor. “What could be cooler than that? But what could be more disrespectful to James Baldwin than to claim that you made him, when you didn’t?”

Larrimore and Public Engagement history professor Julia Foulkes have worked for the past 10 years with the Archives and Special Collections office to research The New School’s past, and educate its community through lectures, courses, and a website.

The question of James Baldwin’s presence on campus has been a debate for some time. Foulkes wrote Public Seminar essay in Dec. 2017 examining the evidence that Baldwin had ever attended.

“From all available evidence unearthed so far, Baldwin never took a course at The New School,” Foulkes wrote. “The Baldwin estate had agreed that the university could quote him on its website but the estate could not verify that he had attended the school.”

However, the Free Press located a biography on Baldwin written by his long-time friend, journalist William J. Weatherby, that describes an interview where Baldwin himself described how the two met.

“He thought it was at the New School for Social Research, where he was taking a class on the theatre with the dream of writing a long-running broadway play,” Weatherby wrote, and quoted Baldwin: “I think I was about twenty so it was probably around 1944,” Baldwin said. “I think Marlon [Brando] was hanging out at the New School, too.”

Baldwin likely took a course at the Dramatic Workshop, a program that Brando and three other celebrity figures from the video attended that The New School cut ties with in 1949 after launching it in 1940. Foulkes had heard rumors of this, and nonetheless expressed concern at the use of Baldwin’s reputation to bolster The New School.

“I think we tread on his image at our own peril,” said Foulkes. “Especially considering that for the first 50 years of its existence, The New School did not have a consistent record of social justice regarding civil rights, despite a few good moments.”

In response to the Free Press’ inquiry about the new evidence tying Baldwin closer to the university, Foulkes wrote, “I think the question remains as to whether we can call him an ‘alum’—and, most important, claim his standing on racial issues as reflective of our own at the time. The school barely had any students at that point who had a degree from the school (just a few graduate students from the Graduate Faculty); most often, people took a course or two. So I often think in this kind of situation that it’s important to consider whether the person claimed The New School.”

Baldwin and the Dramatic Workshop alumni are not alone among the featured figures in the video with a tenuous connection to the school. The artist Ai Weiwei appears, his photograph and name popping up as the narrator says, “They are the persistent,” despite the fact that he dropped out of Parsons in 1982 after arriving in New York in 1981. He told Time in an Oct. 2012 interview that the school helped him better understand influential artists like Andy Warhol. However, a New Yorker feature about the artist stated that “Parsons was a poor fit. Ai excelled in the studio but hated art history.”

The actor Bradley Cooper also gets a nod in the centennial video. He received his MFA from the Actor’s Studio during the period that it was contracted to The New School from 1994-2005. It severed from The New School and has since been at Pace University.

“If you could talk to Bradley Cooper, he would describe a place that’s almost unrecognizable now,” Larrimore said. “So in some ways it’s disingenuous to say, ‘We’re the place that made Bradley Cooper,’ because we [The New School] don’t do what they did when Bradley Cooper was here as part of the Actor’s Studio.”

The list of questionable relations continues, including civil rights leader W.E.B. DuBois, who taught a grand total of one class at the university in 1946, and Jack Kerouac, who like Baldwin is only confirmed to have briefly taken courses that he never publicly indicated. Their inclusion demonstrates an inclination, not unexpected in a branding campaign, to prioritize celebrity over complexity.

What Does the “100 Years of New” Video Overlook?

The famous figures of the “100 Years of New” video are part of a highlight reel that pulls from a broader, more complex history of The New School’s evolution since 1919. Looking back over a century, there are sharp contrasts between the founders’ vision and the institution of today.

When the university was founded in 1919, its focus was on adult education. “It was going to be unlike other universities,” Larrimore said. “People would keep coming as long as there were things they needed to learn: ‘from age 30 to age 80,’ they [the founders] said. Not for four years, not for six years, not to get a degree at all. That was the vision. Adult education was central to what The New School was about.”

This is partly explains why only a fraction of the alumni referenced in the centennial video ever received degrees from The New School. The first full-time Bachelor of Arts undergraduate program, which would eventually become Eugene Lang College, began in the 1970s. Moreover, the New School’s self-narrative does not mention how events in the school’s evolution abruptly changed its structure, markedly the establishment of the University in Exile and the acquisition of Parsons.

“[The Parsons Acquisition] came as a surprise and happened very quickly,” Foulkes said. “At the time [The New School] was taking on experimental undergraduate programs, and Parsons was just another one to conglomerate. It had been floundering financially, and no one thought it would take on the importance that it did in 10 years. As it began to take off, the school helped the university stay afloat financially.”

Larrimore said that “the founders were trying very hard not to make a university” in 1919 and that there was “no particular interest in design” at The New School before acquiring Parsons in 1970.

Clearly, the New School is not obligated to acknowledge every twist and turn in 100 years of history within a two-minute video. The university acknowledges its past on its website. “The New School was founded century ago [sic] in New York City by a small group of prominent American intellectuals and educators who were frustrated by the intellectual timidity of traditional colleges,” the website’s history page states. “The university has grown to include five colleges, with courses that reflect the founders’ interest in the emerging social sciences, international affairs, liberal arts, history, and philosophy, as well as art, design, management, and performing arts”.

“For the purpose of a centennial, you don’t want to tell a complicated story, because you’re talking to people who aren’t interested in history, and they’re not going to be interested in history next year either,” Larrimore said. “So the video was fine for that, and the various centennial events are fine for that, but they don’t tell what really happened.”

For now, those interested in a more in-depth version of New School history can rely on the knowledge being rediscovered and published by the university’s historians.

“The magic of The New School is how it happened,” Larrimore said. “How did this place, that was set up to be one thing, become something else, become this place where all these other unexpected things have happened?”