At the age of 21, the act of voting seems like a right of passage—another milestone for entering adulthood. I believe every American should exercise their right to vote and create change in our democracy.

When I went to the polls to vote in the 2016 presidential election, I felt like I put a checkmark on this act and didn’t think about it again.

At first, when midterm elections came around in November 2018, I didn’t think much of it.

But in this election, my vote counted directly toward my older brother getting his right to vote back.

Here’s how it happened:

When it was time to start thinking about the midterm elections, I requested an absentee ballot. When I went home for a weekend in the beginning of the semester, I filled out who I wanted to win for governor and Senate before giving my ballot to my mother, so she could fill out the state-level candidates and legislature. I signed it, left it for her to mail out and didn’t think about it again. I felt no excitement or urgency about voting. I was already registered. I had voted before; there was nothing else to care about.

It wasn’t until the Sunday before election night that I began to care. My mother called me, frantic, telling me she forgot to mail out my absentee ballot. She wanted me to fly home Monday night, so I could vote Tuesday morning. I told her it wasn’t that serious; I wasn’t going to fly all the way back to Tampa, Florida just to fill in bubbles.

Still, being from Florida, I am aware of how especially important elections are. I know that swing states, like Florida and Iowa, have the ability to change the outcomes of elections, such as the controversial 2000 presidential election between Democratic candidate Al Gore and George W. Bush. This really gives the people that live in those places a stronger voice. Yet, my voice and vote didn’t seem important enough for me to jump on a plane.

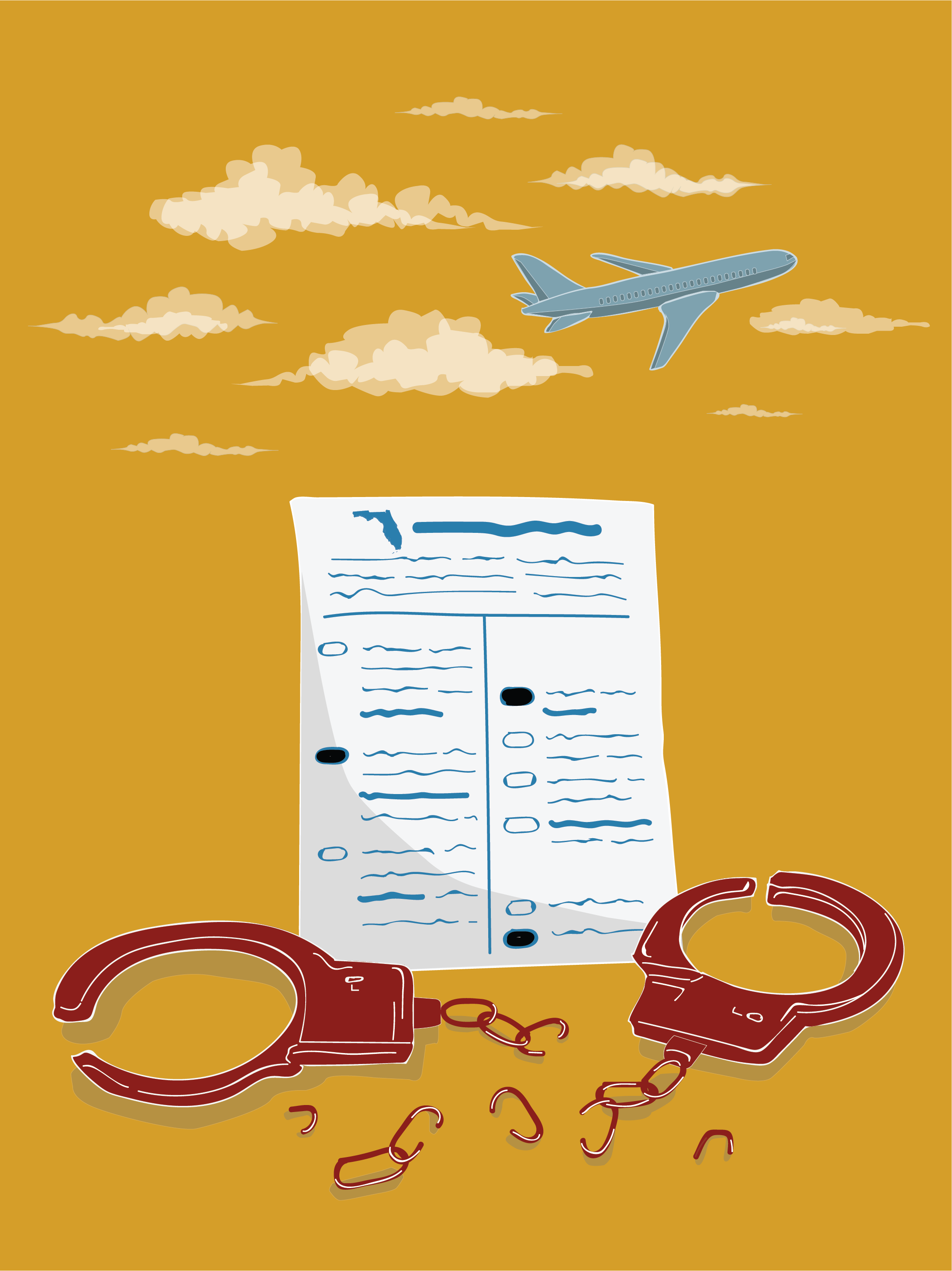

But my mom disagreed. She told me to look up “Florida Amendment Four,” and then I would understand. After looking it up, I realized I had to go home. I packed a bag and brought it with me to school Monday morning, and after my last class ended at 5:30 p.m., I hopped on the R train to catch the last flight out of LaGuardia Airport to Tampa, FL.

On Tuesday, Nov. 6, I was among the 5.13 million people who cast a “yes” vote on Amendment 4. The amendment “restore[s] the voting rights of Floridians with felony convictions,” as reported by Florida Election Watch.

The amendment passed. As a result, an additional 1.4 million people will be able to vote in the next election. My brother is among those people.

My older brother, at the age of 19, lost the right to join the military, receive federal aid for college, travel abroad and vote. He made a stupid choice that landed him in a state prison for a nonviolent crime. Now, almost 24, my brother was unable to finish college and has never had the chance to exercise his right to vote.

The prison system was made to punish and rehabilitate people for their crimes. If the prison and criminal justice system really did rehabilitate ex-cons, they should be able to transition back into society without a constant reminder of the crimes they already paid the time for. Just because someone made a bad choice doesn’t mean they shouldn’t have a say in what the society they still have to live in should be like.

For me, traveling more than 1,000 miles to vote on this amendment was more important than any governor’s or Senate race. I’ve always thought there were flaws in the criminal justice system and in how ex-felons are treated when they leave jail or prison. My brother isn’t a bad person; he just made a bad choice. He spent a year of his life paying for that choice, and he still continues to pay for it every time he applies for a job and the question, “Have you ever committed a felony?” appears.

With the new Amendment 4, there is one less thing my brother, and other felons, will have to pay for. My brother, along with 1.4 million people, will be able to have his voice heard and his vote count. The presidential election of 2020 will be his and many others’ first time ever heading to the polls.

Under the revised amendment, someone who is convicted of a felony now has the right to vote “after they complete all terms of their sentence including parole or probation.” Those who have been convicted of murder and sexual offense are still unable to vote, unless the “Governor and Cabinet restore their voting rights on a case by case basis.”

Casting my vote for Amendment 4 made all the difference for me and my family. I know things won’t change overnight for my brother and people like him, but this is a start, and I’m glad I was able to be a part of that change.

Illustration by Olivia Heller