There are few food items so ubiquitous to American cuisine as the burger. In New York City, prices range from the McDonald’s classic at an affordable $1.00 to the Spotted Pig’s infamous char-grilled burger, which goes for $26. The New School’s own burger sits in the middle at a controversial $10.99.

New School Dining Services has, in the last four years, undergone significant changes. Anyone watching has seen the extreme makeover that transpired with the opening of the University Center in 2014. Suddenly, organic, free range, sustainably-sourced options were available to students at a cost, and since then, prices have risen significantly, reflective of the higher quality ingredients and sustainable farming practices that became part of their procurement plan.

Many students felt and continue to feel the rising prices were an unnecessary frill geared towards the more affluent in the student body, especially since the 2014-2015 school year automatically enrolled Kerrey Hall residents in a $1,800 meal plan.

“Our entire mission is to be fiscally responsible and to break even,” said Jessica Roberts, the former director of sustainability. “We only manage to a bottom line of zero, if possible, we are not for profit.”

Roberts, whose position was not filled after her departure in early March, had built a sustainability program with the help of interns from across the university over the past four years.

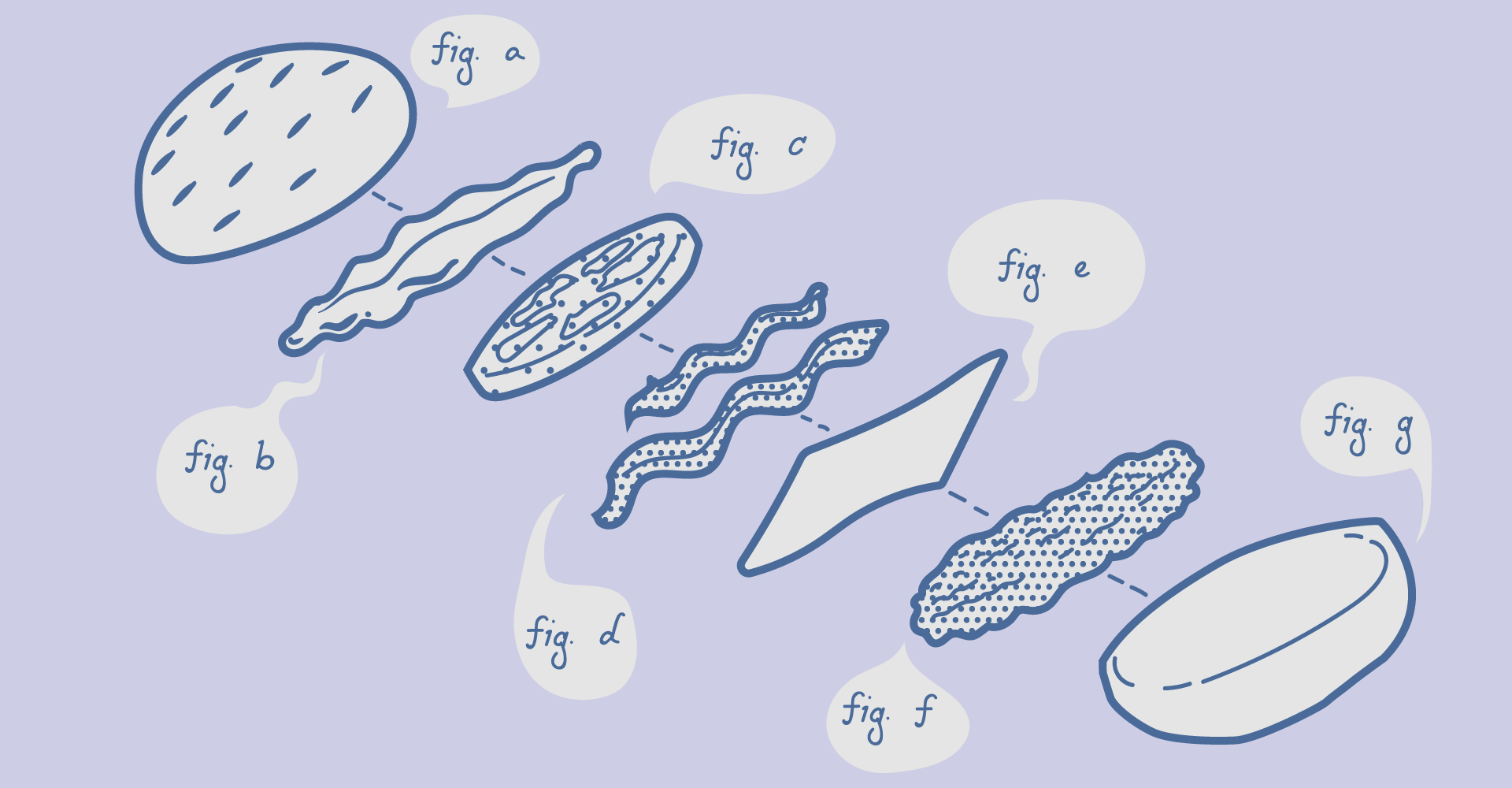

The university’s shift to responsible food sourcing, and corresponding increase in food prices, is a product of heightened attention to various ethical standards. Fair wages, employee benefits, and company transparency are considered just as heavily as ecological soundness and environmental sustainability. As is demonstrated by the burger breakdown below, such values are embodied in a variety of ways, all of which ensure a high standard of care for the environment, producer, employee, and consumer. However, with Roberts’s departure, some close to the project are worried these high standards may not continue to be upheld.

Gregory Herrera, Assistant Director of Business Development, has taken on many of the administrative responsibilities previously held by Roberts while juggling his previous duties as well. Though Roberts is no longer at the helm, her policies and procurement models will continue to guide TNS Dining services for now, according to Herrera.

“There isn’t really a clear answer,” Herrera said regarding the reason for Robert’s departure, “it was just a very natural transition.”

At the same time of Roberts’s departure, the TNS Food and Sustainability platform website dedicated specifically to information about what students are eating and paying for in TNS food spaces became inactive. A new website, in its place, has since gone active.

As an entry model proposed by The New School’s Dining and Sustainability Interns, Dining Services follows the rules of the Real Food Challenge, which pledges to source from 20 percent “Real Food” by the year 2020.

The Real Food Challenge website defines “Real Food” as “true and actual; not artificial … food which truly nourishes producers, consumers, communities and the earth.” “Real Food” is measured by a series of metrics, or guidelines, broken down into four categories: local & community based, fair, ecologically sound, and humane. Every food prepared or sold as part of Dining Services, under Roberts, was measured against these standards.

Roberts and her interns use a system of colors as indicators of how well various food and ingredients meet the Real Food Challenge’s metrics. For example, a green comestible is considered “Real Food,” whereas a red comestible indicates processed, industrially produced food. Roberts and her interns also implemented an orange category to account for food that may not quite meet the stringent requirement of the RFC, but is very close.

For example, the butter that Dining Services uses is sustainably sourced and high quality. However, aiming to keep costs down, they began sourcing from a dairy in California rather than from the local creamery with whom they previously did business. Now, The New School’s butter is not considered local enough to fit into the RFC’s green metric, but could be considered a part of The New School’s orange metric.

Under Roberts and her interns, the New School Dining Services was operating at 25 percent “Real Food” with an unofficial goal of 30 percent “Real Food.” However, as of April, The New School is not listed on the RFC website, meaning they are not a signing member of the Real Food Challenge.

Equally important to the sustainability team is waste management. An earlier article by NSFP outlined the procedures in place to handle waste management.

Currently, The New School is looking for a reliable and well-suited partner to aid in the pickup of leftover food for donation, according to Apourva Muthukumar, a Sustainability and Waste Management Intern working under Roberts. Food that cannot be donated is composted.

Exact metrics regarding food waste management were not given after multiple requests to the parent company of Chartwells, which oversees The New School’s dining program and a variety of other university dining programs throughout the country.

The procurement model in place sources from a range of small, local, sustainable farmers, as depicted by the map graphics flashing on the screens in the UC dining hall. Another consideration in TNS’s sourcing is the labor model.

“Labor is often not considered in other environments and especially not fair wages, not health care, not benefit packages, not paid holidays,” Roberts explained, “also on top of that, we look at all our partnerships, and see if their ideas match our own and the mission of The New School overall.”

***

To break down the sourcing chain, we’ve followed the procurement line of one of the UC dining hall’s most popular dishes, the burger.

THE BURGER: $10.99

THE BUN

Queens-based Leaven and Co., originally founded as Rollo Mio, supplies artisanal breads and baked goods to the New York area. This is where TNS Dining Services sources burger buns from. They have a longstanding partnership with City Harvest through which they donate more than 70,000 pounds of bread a year to help feed the hungry. Leaven and Co. uses a variety of craft baking techniques that aim to improve the flavor and quality of their products such as focusing on the use of leaven-based doughs that have longer shelf-lives and are easier to digest.

THE MEAT

The ground beef comes from one of two places: Fleisher’s Craft Butchery in Brooklyn or Sir William Farm in Craryville, New York & Sugar Hill in Pine Plains, New York.

Fleisher’s is a craft butchery specializing in nose-to-tail practices, meaning that no part of the animal goes unused, and all of the butchery is done by hand. Cuts of meat that humans don’t eat, for example, are turned into a dog treats. They source meat only from local farms and make sure that the animals have to travel no more than one hour from pasture to slaughter.

Additionally, they employ only the most humane of methods in both their animal husbandry and slaughter practices.

Hudson Valley Harvest, the local wholesale distributor operating out of the Hudson Valley is the company from which the university sources Sir William Farm and Sugar Hill’s meat. Brant Shapiro, Senior Account Manager at Hudson Valley Harvest, expressed similar values to those upheld by Fleisher’s. Shapiro said, “All of the beef we [sell] is pasture raised, without the use of sub-therapeutic antibiotics, or growth hormones. None of the farms we work raise veal, and all of our meat is slaughtered at Hilltown Pork, a Family owned Animal Welfare Approved Slaughter House in Caanan, New York.”

THE LETTUCE & TOMATO

The produce within the burger is sourced from a larger scale distributor called Baldor. Much like Hudson Valley Harvest, Baldor sources from a variety of different farms, but unlike Hudson Valley, they source both locally and globally.

THE CHEESE

An example of an ingredient that falls into the orange metric is the sharp cheddar cheese, sourced from Cabot Creamery in Vermont.

“We know it’s a cooperative, they aren’t technically local, they have some disqualifiers because of distribution, but for us they actually fit a sustainability metric and we partner with them,” Roberts said on the partnership with Cabot.

The co-op system means it is member controlled and operated by a network of farms. The farms practice sustainable and ethical farming with their cows and their land and operate under the guidelines of “Farmers Assuring Responsible Management,” or FARM.

THE FRIES

Black Horse Farms, located in Athens, New York, defines itself as a family-run produce farm, gourmet market, country farm and garden center. The farm is USDA GAP (Good Agricultural Practices) certified and all produce is grown free of GMO seeds. An everything-by-hand ethos, similar to that embodied by Fleisher’s, is at the core of Black Horse Farms’s operations. For example, each potato that you eat in the form of a crispy, salty, oil-kissed fry was cut and peeled by hand, on the farm where it was grown.

“They get handcut [and] potatoes come in every single day,” confirmed Roberts, who also expressed that Black Horse runs a highly ethical farm and is a very reliable partner.