After three hours of non-stop “Gilmore Girls” I decided to take a break and check Facebook on Nov. 26. The first post to come up on my feed was simply, “Fidel Castro is dead.”

Though I had heard that phrase too many times before, this time it seemed to stick. The first person I called was my mom.

It was 12:37 a.m. and she would most likely be asleep, but this was something that couldn’t wait.

“Se murio Fidel,” I said.

She seemed to wake up a bit more and said, “le tenia que tocar algun dia.” It had to happen to him some day.

It obviously didn’t take long for the news to spread. For a while, there wasn’t a single post on my Facebook feed that wasn’t a live video of Cubans celebrating in Miami’s Little Havana or reaction videos of various family members. For all Cuban exiles, this was the most joyous occasion.

The next morning I was talking to a non-Cuban friend of mine who said she was confused about how she should feel. I didn’t understand the confusion. The fact was that the man who had held my family’s home country in a chokehold, who took away the businesses my great-grandmother helped build, who locked away my grandfather for years, was dead.

My friend wasn’t alone in her sentiment. A lot of my fellow New School classmates and colleagues seemed to also be conflicted because his death signified the last revolutionary of the West.

Many were talking about how his legacy was that of equality on the island, of medical, scientific, and educational progress. These are points that I cannot dispute, but there are no grounds for the romanticization of the country’s brutal dictator.

It is worth pointing out the numerous imprisonments, murders, and tortures done under his rule. In fact, according to the Washington Post, there were so many executions and disappearances that an exact number has not been discerned. Under his regime he killed more of his own people than any other Latin American dictator in history. There were people who still saw his revolution as righteous.

Among Castro’s rebels was a man I would later know to be my grandfather. He fought for a cause he believed to be just.

But my mother was barely a year old when my grandfather became a political prisoner for wanting to leave the country.

My grandfather remained behind bars for 3 years, while my grandmother took care of six children, made and sold nail polish illegally to make ends meet.

Even Castro’s championship of black liberation and racial equality is disputed by his actual treatment of black Cubans on the island. Castro didn’t suddenly end white supremacy, it persisted even after his revolution. Roberto Zurbano, former head of Cuban publisher Casa de las Americas, wrote for the New York Times, “racism in Cuba has been concealed and reinforced in part because it isn’t talked about. The government hasn’t allowed racial prejudice to be debated or confronted politically or culturally, often pretending instead as though it didn’t exist.”

The disenfranchised still can’t seem to find their voice.

His influence was not just overwhelming but invasive.

My mother told me that when you put in a request to leave the country a government agent would come to your house and take inventory of every little thing you owned. If something were to break, they had to leave it as is until they would do inventory again.

By May 1980, with a fully filled out request to leave the country, my family had packed everything. They kept the clothes on their backs and a spare set of shirts.

All their other belongings had been given away to family friends and neighbors.

On May 19 of that year, my family got a call to leave the house. They were to stand outside, while their house was sealed off and inspected by some anonymous government officials. They stood outside all day.

At around 10 p.m. a call came in from Havana. All previous political prisoners were to go into their homes and not leave until further instructions.

My family was finally able to leave Cuba 15 years later.

Staying in Cuba those years was not easy. Since it was known that they wanted to leave the country everyone in the town saw them as the enemy. Even the closest of friends would look at them with derision.

There were times, my mom remembers, that stones and eggs were thrown at their door.

I still haven’t gone back to Miami or seen my family since Castro’s death. I think that his death will continue to be celebrated by the exile community whether people find it disrespectful or confusing, he has hurt too many and destroyed enough lives for it to not feel like a satisfying sigh of relief. Many have died waiting for this day to come, including my grandfather who only got to live in the United States for about a year before his own death.

I hope that my family will be able to go back and visit their island and experience it with new eyes. I one day hope that “Cuba libre,” a free Cuba, isn’t just a fanciful chant, but a solid truth.

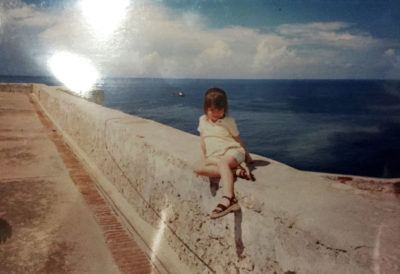

Photos from Odalis Garcia

Odalis is a senior studying Journalism + Design at Lang and the social media manager of The New School Free Press. She spends time watching all of the TV shows and likes to yell about them to her friends, and occasionally writes about it. She is originally from Puerto Rico but calls Miami home (#Miss305) and is very passionate about Cuban food, empanadas, and the salsa dancing emoji.