For people around the world, life has taken a new shape amidst the outbreak of COVID-19. Governments have ordered people to stay home and wear protective masks in public, countries have closed their borders, schools have sent their students home, remote work and learning is becoming a new normal, businesses struggle as they are left with no option but to shut down. Discussion of re-opening businesses in the U.S. is underway and some states have begun taking steps to do so, even as cases of COVID-19 climb and deaths continue to add up.

As the situation rapidly evolves, the world scientific community continues to learn about and study SARS-CoV-2 — the virus that causes the disease known as COVID-19. Here is what we know about the novel coronavirus:

Let’s begin with the basics. What is a virus?

Viruses are not visible to the human eye and are much smaller than bacteria, yet their impact is monumental. They have the power to make humans fall ill and, in some cases, die.

“A virus is a small package of genes that can reproduce only when it gets inside another cell. Sometimes they can cause illness and most of the time they don’t,” said Vincent Racaniello, Higgins Professor of Microbiology & Immunology at Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons.

To even see what a virus looks like, one can’t use a normal microscope, but must use a high-powered electron microscope, said Racaniello.

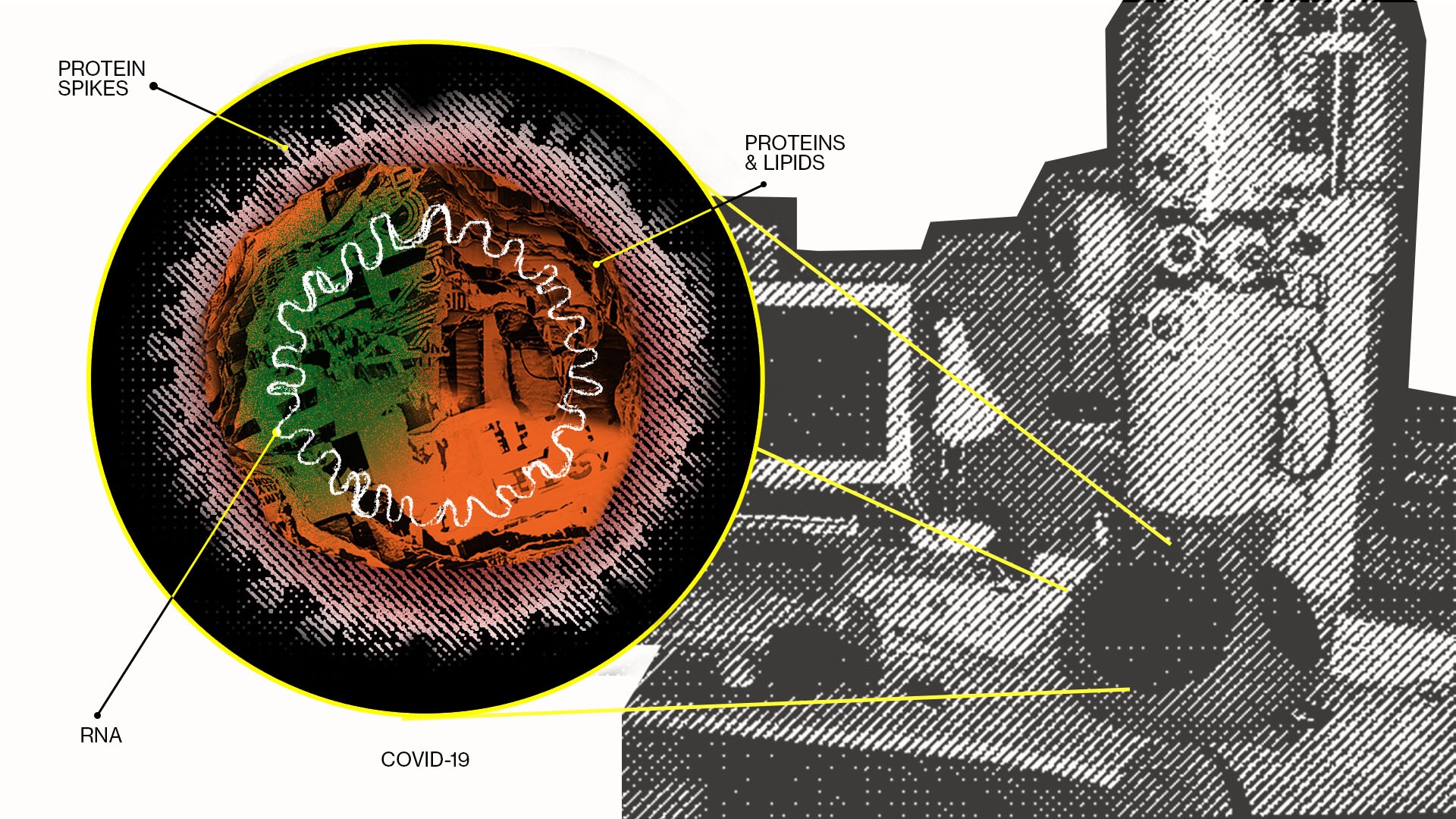

On the microscopic level, viruses can come in a variety of different shapes and sizes and are generally composed of two components: a genetic material molecule, like DNA or RNA, and a protein coat called a ‘capsid,’ which functions as a protective shield for the genetic material.

The virus that we see today, SARS-CoV-2, is part of the coronavirus family, which is a large group of viruses that cause upper-respiratory tract illnesses, like the common cold. Coronavirus gets its name from the Latin word for crown, corona, because viruses from that family have a spiky protein coat that resembles a crown.

Some viruses, like the coronavirus, are surrounded by a lipid membrane, a layer that serves as another protective barrier. These layers shield the virus from whatever it encounters.

Because SARS-CoV-2 is covered in a lipid layer, the virus can disintegrate when it’s exposed to soap and water — a good reason to wash your hands with soap and water for 20 to 30 seconds multiple times a day.

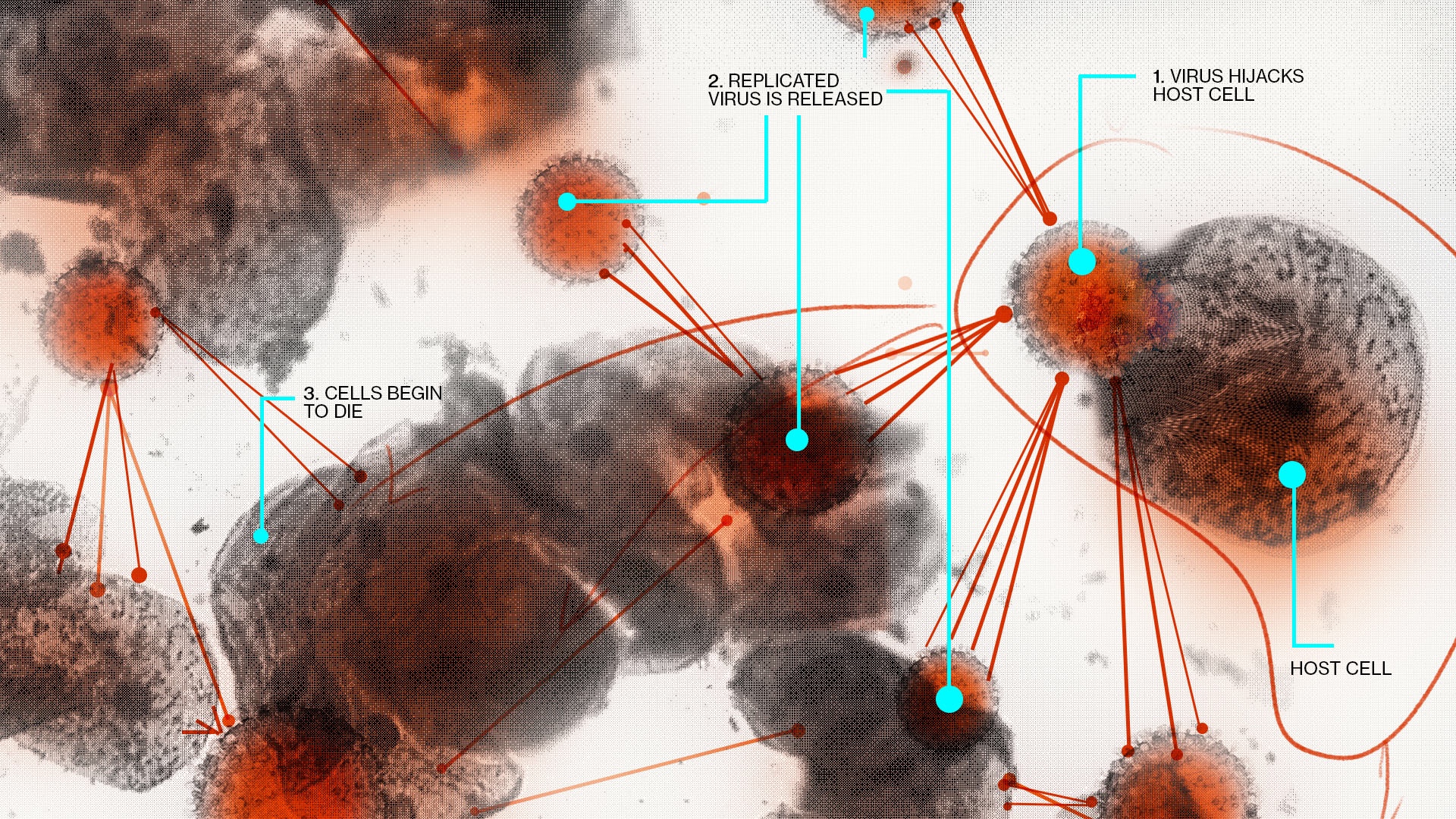

How do viruses work?

“They need to get inside of our cells to reproduce. They are completely parasitic,” said Davida Smyth, Associate Professor of Natural Sciences at Eugene Lang. The technical term for these viruses are “obligate intracellular parasites,” only capable of reproducing inside a host.

The novel coronavirus targets cells throughout the respiratory system, including the lungs, and hijacks the cells by fusing with the lipid membranes of the host’s cells and then releasing viral RNA to self-replicate inside the cell.

SARS-CoV-2 is an RNA virus, meaning the virus is composed of RNA (or ribonucleic acid) as its genetic material. RNA viruses are less stable than DNA viruses and are more susceptible to mutations as they replicate. These mutations can potentially change the behaviour of the virus.

Once hijacked, the host cell generates proteins that continuously reproduce the virus; more than a million copies can be released from a single infected cell. Eventually, the infected cell bursts from the millions of copies of viruses within it — releasing them into the host — and then the cell dies.

As the infection advances, the cells in the host’s body continue to die and the body will produce an immune response to attempt to fight off the virus. Those fever and chills a person sick with COVID-19 gets are the immune system at work.

The immune system also produces antibodies, proteins that are made by the body which are unique and specific to the invading pathogens. Tens to hundreds to millions of antibodies are produced and then bind to and inactivate the viruses in the body.

After an infection, the cells which produce the antibodies multiply and increase proportionally and which protects the body from future infection, a feature known as “immunological memory.” However, experts still do not know whether antibodies from SARS-CoV-2 can provide immunity against getting infected again.

How do viruses spread?

The most common way for the coronavirus to spread and infect others is when a person comes into contact with infected respiratory droplets released from our mouth when we speak, eat, sneeze, talk or breath. These droplets can travel through the air and land on another person or on surfaces around the infected individual, like a door handle.

Another common way for the virus to spread is if an infected person touches their nose or mouth with their hands and then touches a surface that humans use a lot, like a store counter or credit card keypad. If another person touches that infected surface they can transfer the virus from hands to face easily. Humans touch their face a lot more than they realize.

“You know, we are always touching our faces. Don’t do it until you can wash your hands. I wash my hands a lot, I minimize my contact with people, and I’m trying to stay home as much as I can. My whole family is at home and they’re not going out and I’m trying to do the same,” said Racaniello, who works in a lab studying viruses and teaches a virology course at Columbia University in the spring.

“They’re usually not floating around in the air unless someone’s around. So if you’re just walking down the sidewalk and there’s nobody around you, there are not going to be any viruses that can harm you,” said Racaniello.

A recent study of aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 from the New England Journal of Medicine found that SARS-CoV-2 was viable in respiratory droplets for up to three hours, on cardboard for up to 24 hours and on plastic and steel for up to two to three days.

If you want to efficiently clean a surface, Racaniello recommends using a bleach wipe, alcohol, or just regular soap. “They [viruses] are not impossible,” said Racaniello on killing the virus.

At the beginning of the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in the U.S. those who were initially infected were coming from areas where the outbreak was more severe, like China and Iran, but now about 99% of infections in the U.S. are a result of community spread, said Racaniello.

Community spread occurs when people become infected without any knowledge of coming into contact with someone who has the disease. People cannot trace the source of their infection.

“That’s why the separation is actually working,” says Smyth. “If you keep six feet away from somebody, you’re not likely to cough on them directly.”

But it is also believed that people who are asymptomatic — who carry the virus but don’t exhibit symptoms — play a major role in transmission. “If they’re just talking to you and they don’t have any symptoms, that’s where community spread comes in,” said Smyth. “That can happen at a quick staggering rate before anyone would even know. That’s why testing is so important.”

What makes SARS-CoV-2 unique?

This isn’t the first time the world has seen a coronavirus outbreak. In 2003 there was the first reported severe acute respiratory syndrome, SARS, outbreak in China, and the Middle East respiratory syndrome, MERS, has been circulating in the Arabian Peninsula since 2013, according to Racaniello.

All three of coronaviruses originated from animals like camels and bats, and found their way to infect humans.

But the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak is different from the previous MERS and SARS outbreaks.

A key characteristic is that the virus does not make a lot of people very ill and infected people can feel no symptoms at all. “Eighty percent are not very sick so they don’t seek any health care and so they’re walking around, shedding virus,” said Racaniello.

On top of that, this strain of coronavirus is novel, brand new, meaning no one has ever been infected with this specific strain of virus before. This means that there is no immunity so the virus spreads easily. Compared with the common cold and the flu, immunity varies for each person.

“So, that’s a perfect storm, on top of which it is spread by respiratory droplets. So it’s people walking around just talking, spreading this virus,” said Racaniello.

So how infectious is SARS-CoV-2 exactly? The virus is slightly more infectious than normal seasonal influenza or pandemic influenza that we see every year, Racaniello pointed out. An infected individual with COVID-19 can infect up to two to three people at a time, whereas a person infected with the seasonal flu can infect up to one or two other people.

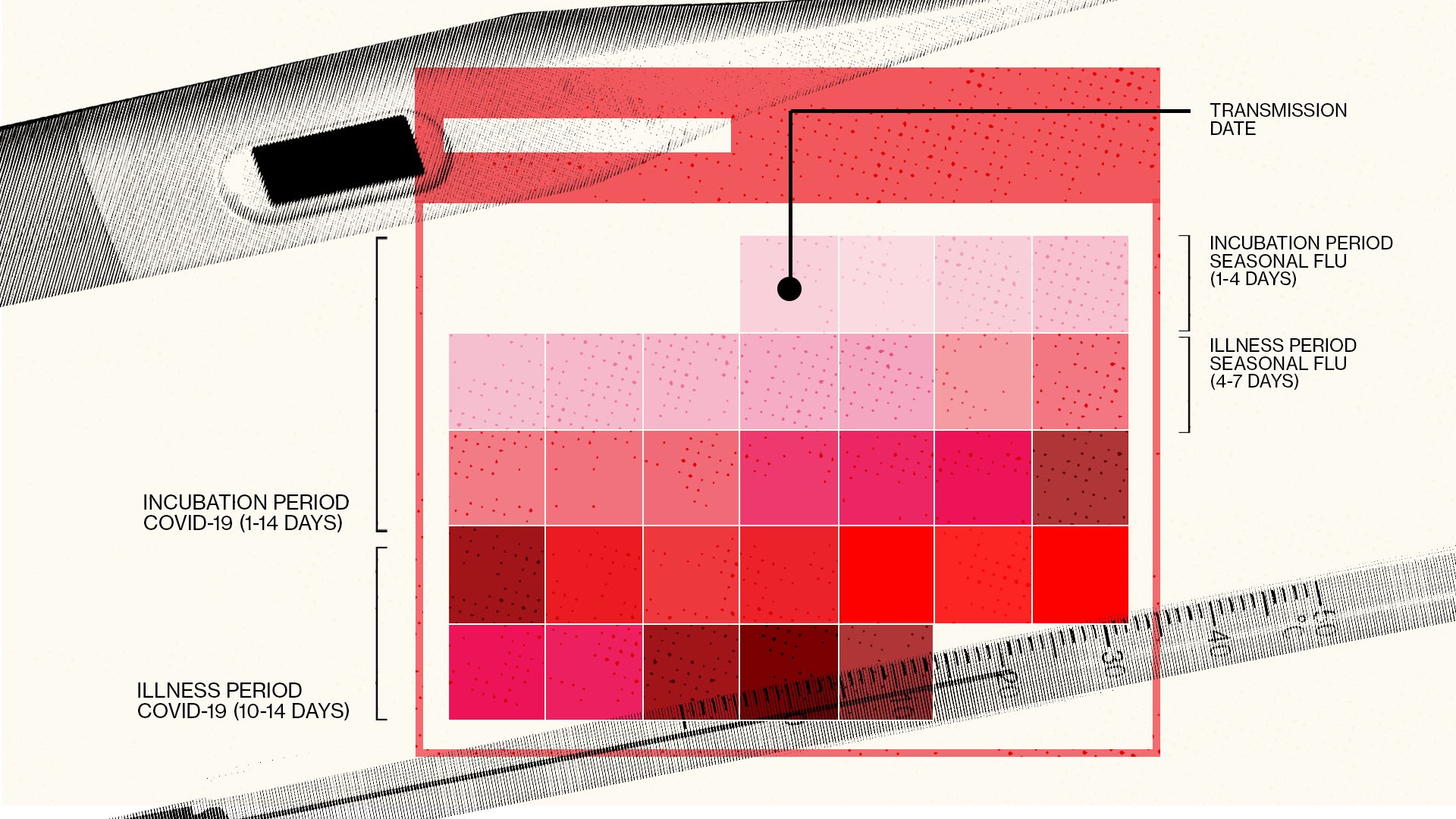

Many people have been comparing COVID-19/SARS-Cov-2 to the common flu, but it is not a flu — it just can result in flu-like symptoms.

The incubation period, or the time period between initial infection and appearance of symptoms, for the disease caused by the coronavirus, is another factor that differentiates it from other viruses. COVID-19 has a 14-day incubation period, while the seasonal flu takes 1-4 days.

How can you avoid getting yourself and others sick?

Such a routine act as washing your hands couldn’t possibly be enough to get rid of the virus, could it? But in fact, it only takes 20 to 30 seconds for the tails of soap molecules to infiltrate and break down the shell of oily lipids that surround the virus.

Experts recommend social distancing and self-quarantining to slow the spread, even if you are not presenting any symptoms.

If you are feeling sick, you should wear a face mask around other people, like, for example, at the pharmacy, doctors office, or if you are sharing a room. The body attempts to release the virus that is infecting your body through coughing and sneezing so it is important for people who are sick to wear masks.

The CDC is advising people to use simple, even home-made, cloth masks “to slow the spread of the virus and help people who may have the virus and do not know it from transmitting it to others,” according to the CDC website.

The CDC considers surgical masks or N-95 respirators as critical supplies and recommend that these types of masks be reserved for healthcare workers and other first responders.

Another way to avoid the spread of virus and disease is through contact tracing, a process that pinpoints every person an infected person has been in contact with in order to trace the spread of the disease. When an individual has been contacted they are advised on the risk imposed on themselves and others and may be asked to self-quarantine to avoid the further spread of the disease.