This article appears in our October print issue. You can pick up a copy on newsstands around campus, or at our newsroom in room 520 in the University Center.

____________________________________________________________________

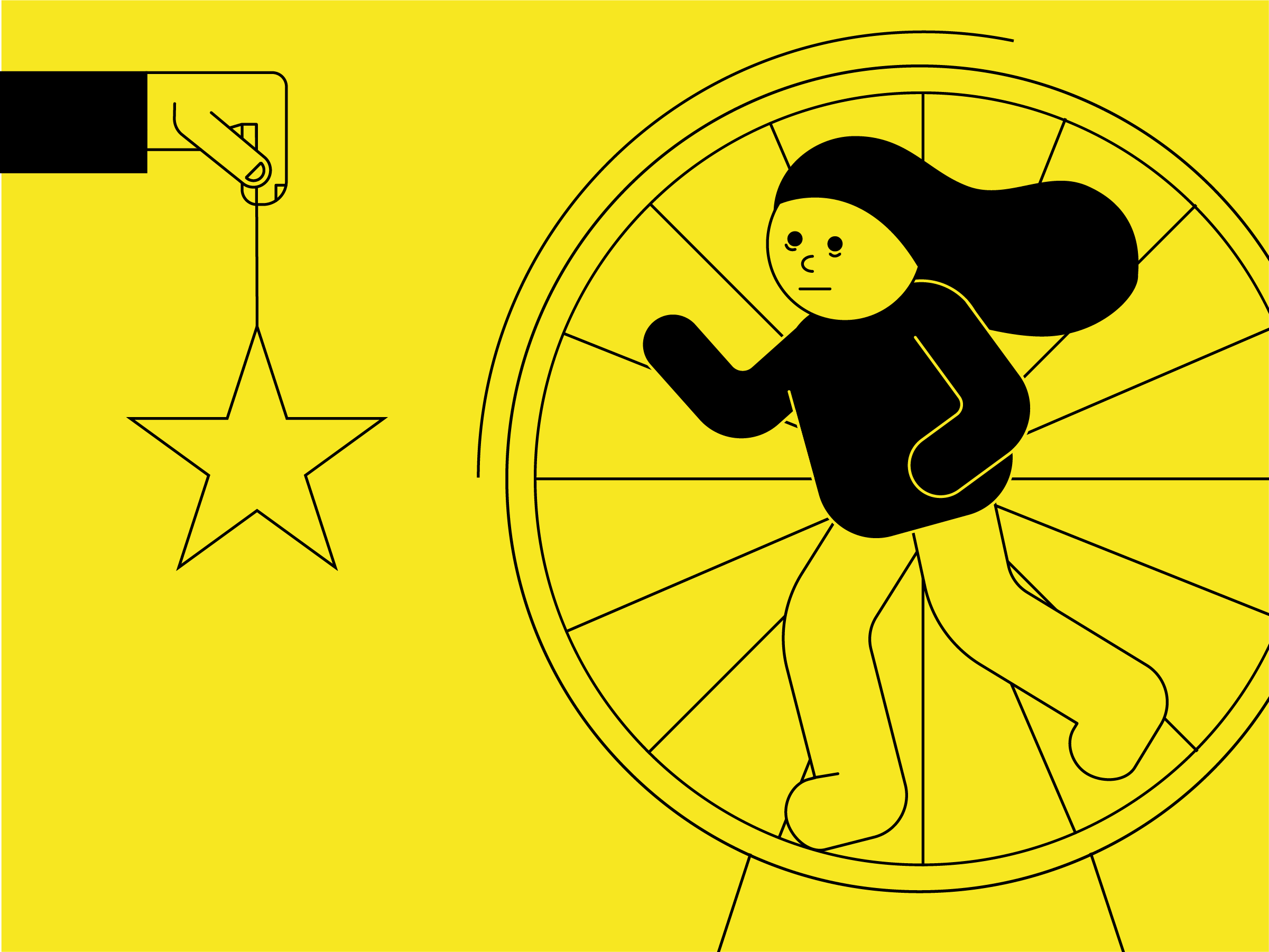

My heart sank and my throat caught – I had just found out that the unpaid internship I did this summer was illegal. 27 long hours a week (which I actually negotiated down about a month in) doing social media marketing and writing articles to benefit a for-profit publication in New York City, and, monetarily speaking, I got zilch in return. In fact, I actually ended up losing money on this internship, due to my daily commute and other expenses that would not have existed had I not participated in this “experiential learning opportunity.”

Though I am not critiquing the publication that I interned for, where I learned a lot, I couldn’t help but feel angry at the fact that it seemed I had been taken advantage of. This sort of experience is not uncommon amongst college students, but that does not make it okay. A practice that does not pay people for their time is completely unethical, illegal, inaccessible, and a clear-cut means of exploitation.

The formal “internship” has been around since the late 1960s, but gone are the days of the quintessential, wide-eyed trainee running around grabbing coffee. Interns nowadays do real work. After all, paid or unpaid, the purpose of an internship is to give students industry experience. In 2017 at The New School, according to a fact sheet from Career Services, 58% of graduating students reported having had one internship throughout their time in college. 43% of these internships were unpaid. Marisa Lo Bianco, Senior Director of Career Development and Experience, confirms that The New School is firmly against unpaid internships and believes that they are unethical. Lo Bianco heavily referenced Fact Sheet #71 by the U.S. Department of Labor, which states that if a student is actually an employee (based on certain criteria, which my situation happened to fall under), then it is against the law to not offer some sort of compensation.

An unpaid internship is, for the most part, closed off to anyone who needs to actually be making money. This means that most students doing unpaid internships are well-off enough to afford them, canceling out a whole section of people that fall below a certain socioeconomic status, and contribute to the systematic discrimination of minorities, making unpaid internships an inequitable practice.

And let’s not forget- college is expensive and, naturally, many students are in debt. According to The Federal Reserve, over half of college students in the US took on debt in 2018. That’s a whole lot of college students.

So what can we, as students, teachers, and employers do to make a change within this dysfunctional system?

For students, I would like to stress the importance of doing your own research (as I did not) about what you are entitled to and making your decisions based on that knowledge. As teachers, I would like to emphasize the importance of teaching salary negotiation skills to students, especially students of color, women, and other minority groups, so that the practice of the unpaid internship will slowly dissipate. The American Association of University Women, a non-profit organization that leads salary negotiation workshops for women and girls, will be coming to The New School three times this semester (all further details can be found on HireNew.com).

For employers, I would urge you to remember the reason that you are doing this. You want to train and inspire a young new workforce – dewy and full of bright ideas, remember? Is offering unpaid internships really the way to achieve this?

In a few weeks, millions of laptops will get fired up, resumes will get edited, and notifications will be set for job alerts from indeed.com and others like it. Spring internship season will be upon us, college students. Please be conscientious about what you, as an undergraduate, chose to put your effort toward. Do not overlook the fact that you are the future – soon, it will be up to you to pump new life, substantiated by unique ideas and pointed insight, into the veins of whatever field you choose to pursue. I encourage you to ask questions and reach out for help about how to get the most for your work.