Just one month after models walked the runways at 2013 Tokyo Fashion week, a tragedy enveloped the fashion industry. Over 3,000 miles away, in Dhaka, Bangladesh, the collapse of the Rana Plaza factory building became the worst industrial accident to hit the garment industry. On Apr. 24, 2013, over 1,000 lives were lost and thousands more injured in this avoidable accident.

Thousands of workers resisted entry into the five factories housed in Rana Plaza due to large and dangerous cracks in walls, according to the Institute for Global Labour and Human Rights. Tensions rose when the building’s owner, Sohel Rana, paid and brought gang members into the factory to physically force the workers back into the building.

According Bangladeshi journalist and human rights activist William Gomes, the chief engineer of the state-run Capita Development Corporation, Emdadul Islam, stated that Rana had the building illegally extended to eight stories, past the permitted five stories.

With the growth of the ready-made garment industry in Bangladesh, many ordinary buildings have been converted into high-rise factories. Critics place the blame onto the industry’s pressure to drive profits through the rapid mass production of clothing, pushing safety protocols to the back seat.

Major retailers such as JCPenney, Joe Fresh, Benetton, and Primark were among those manufacturing their products in Rana Plaza.

Laura Sansone, the founder of Textile Lab and a professor of alternative fashion systems at Parsons School of Design, says that the Rana Plaza collapse acted as a catalyst for the fashion industry to reevaluate the production process. “That was an awakening for the fashion industry,” Sansone said.

After the Rana Plaza collapse, consumers, designers, and manufacturers began exploring more conscious and sustainable options.

According to Sansone, sustainable fashion refers to brands and designers who consider the social and environmental implications of the products they create and present to the world. This means scrutinizing all aspects of the product: from the farming and growing of the raw materials, to its manufacturing, transportation, distribution, use, and recycling.

The opposite of this is fast fashion, a more known and widely applied production process in the market today that often disregards these implications for the sake of quantity and profit. These are products that are only around for a season before they are thrown away and replaced.

Companies like Zara, H&M, and Forever21, which mass produce styles and trends seen on runways with low quality materials to sell at a cheaper price point. The demand from consumers to keep up with trends at low prices and the urgency from corporations to meet these needs is a driver of the fast fashion cycle.

Sansone was living on a farm when she became aware of her natural environment and its role in producing textiles. Rural life exposed her to neighboring farms and animals that were generating materials she could use in her work. She eventually gravitated towards natural dyeing and working with regional materials.

Inspired by her time on the farm, and seeing connections with the organic and “slow food” movements Sansone founded Textile Lab in 2009.

Textile Lab supports ethical textile design and production out of the Greenmarket system in New York City. The lab–a mobile kitchen and workstation on wheels–gives her the tools to harvest for dyes at the Greenmarkets and to explore sustainable ways to dye materials. The physical labs were first introduced in her classroom and she currently teaches a course called Community Supported Textiles at Parsons.

Sansone uses the lab to raise consumer awareness about how clothes are made by looking at the lifecycle of materials. She focuses on using byproducts, such as onion skins, beeswax, wool, and leather for her textiles dyes.

Long Island Livestock Company sits on 17 acres of farm in Yaphank, NY, just over an hour drive from Manhattan and the fast fashion frenzy that lines the streets of Broadway and Fifth Avenue.

At the picturesque red farmhouse, where the company was founded by Tabbethia Haubold-Magee over 20 years ago, slow fashion production is well underway.

Echoes of a nearby gun range spilled into her farm while the sheep chomped away at a barrel filled with hay. She refers to her sheep, Mumford, Lily, Jack, and Jill as her “children,” along with the other animals she breeds and raises. She shears the sheep only twice a year to produce fleece and to do public shearing demonstrations. Her real mainstay and speciality are the llamas who live a quick minute walk down a gravel road; they are sheared four times a year.

Her livestock count is always changing, but one thing that isn’t is how she uses their fibers. Haubold-Magee’s business tackles the first stage of production cycle: sourcing materials.

Her passion for shearing has allowed her to travel all over the east coast from March to July to shear fibered animals for other people. She’s also developed a skincare line that uses lanolin, a wax secretion that comes from the sheep’s wool.

Haubold-Magee dedicates tilemuch of her time into building her independent yarn company, both by producing and designing her own yarn. This leads her to form relationships and provide sustainable materials for designers.

She explained that she’s always been contributing to the slow fashion cycle, but only recently through her visits to Parsons, which says it is focused on “designing responsibly, creatively and purposefully,” has she really been made aware of the term itself.

“The whole point of fast fashion is trying to get it out the door faster, trying to bear the trends,” Haubold-Magee said. “The reality is if you’re creating something that isn’t classic, that doesn’t have longevity with what somebody is going to wear, then [the consumer] is just going to throw it out and then they’re going to move onto the next piece.”

This is the vicious cycle that fast fashion imposes and that slow fashion is trying to combat. For Haubold-Magee, having a classic sense of style helps eliminate the urgency to produce trends, a key factor that drives the fast fashion industry.

Haubold-Magee argued that people who have animals and are involved in agriculture have always promoted a “natural way of life.” Larger corporations quickly took note of the terms “natural” and “organic,” and used them, she says, as a marketing ploy for consumers to buy into. The same pattern can be seen with the rise of farm-to-table fashion, she says, with larger corporations marketing their products as sustainable in order to profit from a trend.

“I think that is what’s aggravating for somebody like myself is that people who truly aren’t doing that step up to the plate to use those words and use that promotional pitch,” Haubold-Magee said.

[slideshow_deploy id=’14241′]

Haubold-Magee recalled an incident before she started her own yarn line when she noticed a company who had an image of little black lamb named Andy on all of its packaging. She found it striking that Andy was depicted on multiple packages of yarn, when in reality she knew ‘Andy’ went into producing a small fraction of wood. She argued this was false advertising.

Haubold-Magee aspires to be completely transparent with her production. She explains that if there’s a picture of an animal on her yarn, it tells you whether she sheared all the fibers or the majority of the fibers that went into it. Some of her yarns are sheared at other United States co-ops, so consumers won’t find an animal tag on those.

Ever since the tragedy of the Rana Plaza collapse, sustainable fashion and its different methods of production are pushing to the forefront of the industry. According to a report published in October from McKinsey & Company, “a few apparel business have begun tackling sustainability challenges on their own.” H&M and Levi’s have partnered with I:CO, a recycling provider for used clothing and shoes; Patagonia collects used clothing in its stores and through the mail and also offers repair services for customers to extend the lives of their garments. Despite the gradual progress, designers and slow-fashion producers still face many challenges ahead.

Sansone explains that she noticed an increase in brands wanting to access regional materials to integrate into production, but that it proves difficult for some due to the structure of their businesses.

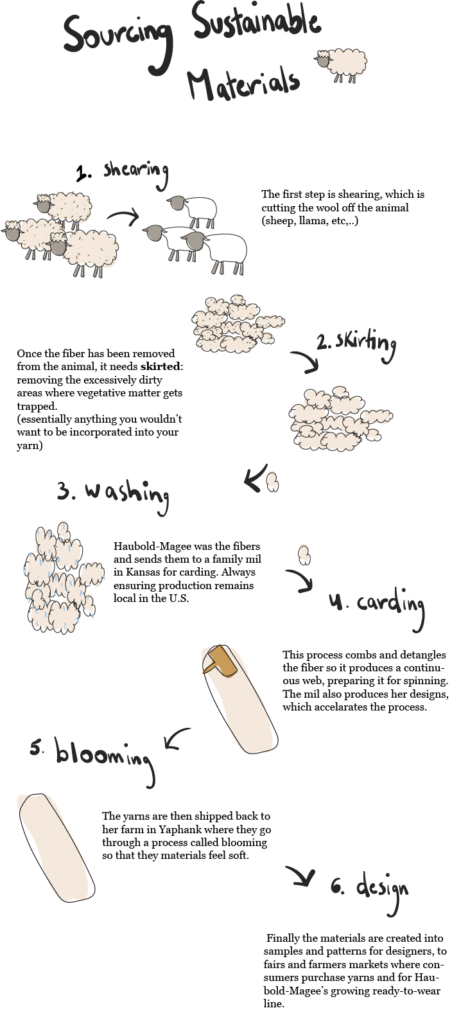

The animal’s wool is cut off.

Once the wool is removed, it needs to be skirted, by removing the excessively dirty areas where vegetative matter is trapped.

Haubold-Magee washes the material and sends it to mill in Kansas for carding

The mill combs and detangles the fiber (now referred to as yarn) to produce a continuous web that is ready for spinning.

The yarn ships back to the farm in Yaphank and undergoes blooming, so that the material feels soft.

The yarn is used to create samples and patterns for designers. Haubold-Magee sells the yarn, and items from her ready-to-wear-line, at fairs and farmers’ markets.

“It’s like taking two different systems and trying to bring them together. So it’s challenging because one operates on profit margin, bottom line sort of economics, and fast turn around; the other is different, it’s about the environment, the earth, and honoring place and people and locality,” she said. This is where Sansone comes in with Textile Lab — to help bridge this method of slow production with brands and designers.

One prominent factor that remains a concern for consumers looking to purchase sustainably is high price points. Haubold-Magee acknowledges that her materials aren’t cheap and understands that not everyone will pay $300 to $350 to make a sweater out of her yarn. By continuing to talk about her company’s story and what goes into the yarns she hopes to show her consumer what they’re paying for.

The questions of “do I really want this?”, “where was it made?”, and “how was it made?” aren’t necessarily considered in the minds of consumers while purchasing a $10 item, she says.

“I think the lowering of price point has really disconnected the consumer from having to ask the types of questions that you ask if you’re sitting in front of an $800 dollar coat,” said Nadine Farag, a fashion blogger and sustainability expert.

In order to press these sort of questions and emphasize the value of their products, designers are starting to pave the way by taking a stand with their brands.

Take James Chapman, a senior at Parsons School of Design who was introduced to Haubold-Magee during his third year. Although his interest in sustainability traces back years, it wasn’t until he paid his first visit to Long Island Livestock Company that it became a reality for him.

The launch of his brand with Jacob McIntyre, his partner and a Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT) graduate, allowed him to incorporate yarn and fiber from Haubold-Magee’s farm into their designs. The Chapman|McIntyre website offers complete transparency into the brand’s ethos, stating that “an important part of our brand identity is being involved in every step of the process, and to support local jobs.”

Another designer is Kristen Avery Luong, the founder of KROMAGNON, which is a sustainable and eco-friendly high street label that debuted at New York Fashion Week in February 2016. Upon graduating from FIT in 2013, Luong knew she wanted to build a sustainable brand centered around materials that were organic and biodegradable.

She believes there is a greater demand for sustainability in fashion but is unsure about how the market will grow. Despite the increase in visibility and demand, Luong only foresees a definite change in the industry if more brands adopt a sustainable model. This would increase competition and lower cost, making sustainable fashion more financially accessible to the average consumer.

Monica Magliari, a senior fashion design student at Parsons School of Design, is currently creating a “high end ethical and sustainable retail store” for her thesis project. She’s in the process of curating the designers eligible for her online store by ensuring complete transparency with their production process. In order for Magliari to include a designer in her store, she wants to know the factory the designer worked with, how much workers were paid, what types of dyes were used, and so on.

Sansone is hopeful that the millennial generation can change the fashion industry. “These kind of things take 30 or 40 years, but the change is underway,” she said. “I’m in it. I see it. I hear it.”

James Chapman is a senior. An earlier version of this article said he graduated.

Sydney is a current Junior studying Journalism & Design at Eugene Lang and the Co-Editor-In-Chief of The New School Free Press. She spends a questionable amount of time responding to emails, remembering coffee orders for her various internships, producing films & frolicking around the Lower East Side where she’s living her New York dream of occupying a bedroom with a brick wall.