Observations of a New School Alumna

I write from Sidi Bou Said, a touristy seaside town outside of the Tunisian capital, which Lonely Planet has informed me was once home to Michel Foucault.

It’s December 8, 2011 — the middle of the last month of this eventful year — and about three days after I had anticipated arriving in Tripoli, Libya.

I came intending to transit through Tunisia: a simple enough thing to do and one that many Libyans did during the years that international flights into Tripoli were suspended because of UN sanctions. It’s not that it’s close, per se; small as Tunisia may look on the map, the drive from Tunis to Tripoli takes around 10 hours — not including time spent waiting to pass through the border at Ras Jdir.

Still, it seemed like a very reasonable plan, and one that might even have involved enjoying some of Tunisia’s nightlife with my cousins. Libyans have long enjoyed vacationing in Tunisia, not least of all because of Tunisia’s comparatively permissive atmosphere for things like drinking and smoking. Tunisians have also visited Libya in turn, many enjoying Libya’s beautiful and often rather empty beaches. In the wake of recently-imposed visa requirements on Egyptian and Moroccan nationals in Libya, Tunisians are still able to enter Libya without advance approval — a sure sign of the two states’ and their peoples’ generally amicable relationship. In a region often dominated by its bigger and louder members — Algeria and Morocco to the West, Egypt (“Mother of the World”) to the east — I’d go so far as to posit that Libyans and Tunisians have tended in the postcolonial era toward a certain solidarity, perhaps based on Tunisia’s relative smallness in size and Libya’s isolation and relative smallness in population.

The upheavals of this year have taken some toll, however. There is, of course, a solidarity to be found in having twin revolutions, successfully overthrowing two entrenched heads of state who were, in fact, friends. This solidarity was most hearteningly displayed by the many Tunisians who lent a hand to the outpouring of Libyan and other refugees fleeing civil war. Still, that same outpouring, and the subsequent return of many via the same road, means the Tunisia-Libya border has had a busy year, undoubtedly exhausting those working at Ras Jdir.

I followed news of the border in the days leading up to my flight from New York to Tunis. There had been some problems: Libyans reported being attacked and robbed by Tunisians, a Tunisian border patrol guard had reportedly been shot by a Libyan “rebel” forcing his way into Tunisia, and Libyan forces had been ordered away from the border by the National Transitional Government (NTC). The border had been closed. I didn’t jump to any conclusions, hoping that the border would be reported as open and moving within a few days.

But upon arrival in Tunis, I found a more general air of concern than I had anticipated. Not only was nearly everyone I spoke to discouraging me from attempting to cross the land border (it was no longer possible for family to enter Tunisia by land to meet me, and Tunis-Tripoli bus service had been suspended), but apparently it was not possible to fly either. When I expressed my bewilderment to a Tunis Air employee — “What does the closure of the border have to do with your flights to Tripoli?” — she kindly brought me up to speed: about two weeks ago, Tunis Air suspended all service to Tripoli after armed people there boarded a plane full of (obviously unarmed) passengers. The men who boarded the plane with their weapons were thowar, she said — revolutionaries — and they came in search of some Gaddafi-loyalists who were trying to flee Libya.

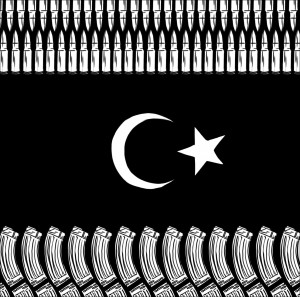

My Tunis Air newswoman referred to the Gaddafi-loyalists as, I’ve learned, Tunisians currently do: with the word kataib. This was rather confusing at first, because in Libya this word is used to refer to any brigades — its literal meaning — including those of the revolutionaries. But this confusion — were they the “good guys” with weapons? or the other guys? — points to the rather confusing, and frightening, situation of the prevalence of arms in Libya right now.

In October, I wrote from Benghazi with my impressions of the situation there. At the end of that visit, after similar difficulties related to scarce flights and conflict-created road blockages as the ones I’m having now, I made it to Tripoli. In the few days that I was able to stay there, it became apparent to me how profoundly differently the cities of Benghazi and Tripoli have experienced the February Revolution. In comparing the two largest Libyan cities, I am of course leaving aside the equally important experiences of people in other parts of Libya, for example and not exclusively, those in Misrata, which was very brutally bombarded by Gaddafi forces from March to May; those in the far-eastern Libyan coastal towns, like Derna and Tobruq, which rose up with strength in the earliest days of the revolution; those in Zintan, who led the battle into Tripoli; those in the Nafusa Mountains, who re-awakened an Amazighi nationalism, dormant (forbidden) for four decades, with amazing vigor; those in Beni Walid and Sirte, who bore the bloody fighting of Muammar Gaddafi’s last days. Still, I give my attention to Tripoli and Benghazi, these being the two cities in which I have had the most experience, and which hold the largest numbers of residents.

Generally speaking, it seems to me that Tripoli has had a much more traumatizing experience of the past 11 months than Benghazi has. This may be more broadly true of the the western coastal areas than the east. I don’t by any means want to imply that Benghazi (and the east) had it easy: Benghazi saw intense, swift and very bloody upheaval after its peaceful protests were violently repressed. Residents there saw death — and much of it, fast. Certainly people were still grieving those losses during my visit in September and October. Yet, there was also much hope; people became very busy finding new ways to organize themselves in the wake of the city’s gain of self-control. This process created a sense of pride: pride in the speed with which the eastern cities had rid themselves of a dictatorship that had for so long seemed untopple-able, pride in the resourcefulness with which people had solved practical problems created by the sudden changes in structure. These experiences created a delicate and imperfect unity.

Tripoli’s experience was much more muted: less dramatic, prolonged, more insidiously violent. People were scared of informers. People watched their friends and siblings arrested and tortured, fleeing to Tunisia, houses raided for having an internet connection. People knew (still know) supporters of Gaddafi’s regime; in Benghazi this blatant support was (is) much less. There was not such a sense of cohesion. A certain resentment arose from other parts of the country, flaming older rivalries. Even the city’s liberation came, while with celebration, also with impatience: What took you guys so long?

These difficulties, combined with the arming of Tripoli residents during the war (Gaddafi is reported to have offered weapons to anyone in the city who could “prove” support to his government — Berbers need not apply) and the influx of armed people who came with the invasion of the city, has meant that Tripoli’s transition continues to be uneasy. There is much pressure on the capital to “get things together,” while the grief of the war is still so fresh and nighttime gunfire still jerks people awake. Part of my week has been coordinating my attempted arrival with a cousin in Tripoli who has much more serious things to worry about. A doctor in Tripoli’s main hospital, he witnessed some of the worst of this year’s horror — orders not to treat “rats” (anti-Gaddafi fighters), gunfights in the hospital. This week’s events were no less frightening; a doctor had been kidnapped by armed men who claimed that he had not given proper treatment to their comrade. Other hospital staff was threatened when they tried to intervene.

I am hopeful about some of the initiatives toward transitional justice that have been started. And it is heartening that Tripoli residents do not seem afraid to be vocal about their demand that the city disarm. I hope that programs to address trauma will become more and more available to people in Libya, including Tripoli.

In the meantime, my own saga is at least apparently resolved: this morning I found a recently available seat on a Libyan Airlines plane to Tripoli Saturday, just in time for the downtown demonstration. Once there, I hope to witness some of the tireless work that people there are doing to work out the larger difficulties of the moment.

Leila Tayeb graduated from The New School’s Graduate Program in International Affairs with an MA in 2006. She recently completed a master’s in Performance Studies (NYU, 2011) and is now doing research on art and gender in the 2011 Libyan Revolution.